Wishful Thinking about Addictions (part 3)

The perils of not knowing the natural history (while pretending that we do)

In a previous post, I discussed the importance of knowing the natural history of a health condition or disease, a concept which refers to the progression of the condition or disease in the affected individual over time, in the absence of treatment.

To illustrate the point, let’s talk about pregnancy, because most of us are familiar with the natural history of pregnancy.1 Bear with me. I’ll keep it short.

First, we all know that pregnancy only occurs in people with certain risk factors, including one or more functioning ovaries to produce eggs (or ova), a uterus, and fallopian tubes connecting their ovaries to their uterus.

Pregnancy results from specific “risky” behaviour, namely vaginal sexual intercourse (or at least close contact) with somebody who produces sperm.

However, having the risk factors and indulging in the risky behaviour doesn’t guarantee conception, which occurs when a sperm fertilizes the egg, creating a zygote.

Over the next week, that zygote journeys down the fallopian tube to the uterus, the cells multiply rapidly, and the zygote becomes a blastocyst. The blastocyst implants in the uterine lining, and then the mother’s body begins producing hormones to support the pregnancy. These hormones can be detected by a pregnancy test.

The blastocyst cells differentiate to form the placenta and the embryo. The embryonic stage lasts about five weeks, during which most of the organs and systems take shape.

Making the rest of the long story short, the fetal stage follows, culminating in labour and then birth, about 38 weeks after conception.

In the absence of complications, the natural history of pregnancy is somewhat predictable. There are known milestones along the way, and we look for them on the history, physical exam, blood tests, ultrasounds, etc. Pregnancy proceeds only in a “forward” direction and at a predictable rate, which is to say that if you are 27 weeks pregnant today then you’ll be 28 weeks pregnant next week, barring any complications.2

Complications can occur along the way. Some are more common than others. We aim to avoid or manage them, with varying success.

Some complications relate to the pregnancy itself. The blastocyst can implants in the fallopian tube, resulting in an ectopic pregnancy. Things can go wrong in the embryonic or fetal stages, resulting in a miscarriage or fetal death. Labour can occur prematurely or be delayed. The birth can be simple or complicated.

Other complications reflect the fact that pregnancy increases the risk of other diseases. For example, being pregnant increase the chance of getting a deep venous thrombosis (a blood clot in the leg veins) or having one of those clots travel to the lungs (a pulmonary embolus).

For pregnancy, we know what the potential complications are, how frequently they occur, and what the untreated outcomes might be, so we can be prepared. In some cases, we try to detect the complications early, when they are easier to manage. For example, the maternal blood pressure can creep up later in the pregnancy, resulting in pre-eclampsia or eclampsia and maternal and/or fetal death. Early detection and intervention has been proven to alter the natural history of some complications and thereby improve the outcome.

Looking at the big picture, you start with a large pool of women, but only some ovulate and even fewer have unprotected intercourse when fertile, so the number of ensuing zygotes is relatively small. Not all zygotes become blastocysts, fewer again successfully implant, and an even smaller number proceed to term, resulting in a baby. So, even though the entire process involves women3 and produces babies, you won’t understand pregnancy if you only study the women who died along the way, or the babies produced.

Knowing the natural history of pregnancy means you know “how it works” and “what to expect” from beginning to end, for ALL of the affected people.

“What to expect” is the layman’s term for “outcomes”. The single outcome that matters to those involved is that the pregnancy results in a healthy mother and baby. Sure, you can measure other things, like whether the right blood tests were done at the right times, but in the end those things will only be of interest to the mother if they affect her health or that of the baby.

I tell you that to tell you this…

Practicing medicine without knowing the natural history of what you are treating is like flying blind. It’s dangerous!

You cannot and should not practice medicine without knowing the natural history of what you are treating, and that means the ENTIRE natural history, not just the possible complications and the end result.

If you haven’t considered who’s at risk, you don’t know who the target of your efforts should be.

If you don’t fully understand what behaviours put them at risk, you won’t know what behaviours to encourage or discourage.

If you don’t know the complications, when they appear, who they affect, and why they affect the people they do, then you won’t know when to look for trouble. Your interventions might be too early, too late, too little, or too much.

When you don’t know what happens in the absence of treatment, you can’t say whether or not your treatment is “better than nothing”, and you run the risk of doing something that is actually worse than doing nothing!

Which brings us back to addictions and overdoses…

Surprisingly (and sadly), when it comes to addictions (and overdoses), despite decades (arguably centuries) of experience, the natural history is NOT well known. Most of what we are told is “true” is actually dogma, “a point of view or tenet put forth as authoritative without adequate grounds”. That being the case, much of what we are told about the “best” public health and treatment approaches is naive at best or dangerous at worst. We don’t know whether the experts’ advice is better or worse than doing nothing.

I thought perhaps this was just a gap in my personal knowledge, but I can assure you that I’ve spent weeks poring over the addictions literature and I’m no wiser.

Along the way, I found plenty of people smarter than I am who have identified the same problem.

“…there are major gaps in our understanding of the clinical course of addiction. A mature science of addiction needs to systematically address the empirical structure of the disorder’s clinical trajectory over time. Current perspectives are largely piecemeal and suffer from a ‘blind men and the elephant’ problem. There are different answers from different vantage points, and a broad and definitive understanding cannot be gleaned.” James MacKillop, PhD

“widely held ideas about addiction are at odds with what research says about addiction, particularly research on the manner in which addiction changes over time and the factors that influence these changes.” Gene M. Heyman, Verna Mims

A brief reminder: What the Experts tell us is “the truth”

The proponents of the Brain Disease Model of Addiction (BDMA) would have us believe that addictions4 are chronic (lifelong) relapsing conditions. Once somebody displays persistent involuntary excessive drug use despite adverse consequences (which include the possibility of death due to overdose), then they have a brain disorder, their condition has gone beyond their own control, they won’t get better without long-term or permanent clinical management, and (with or without treatment) they can expect regular relapses. That is the natural history of addictions, so sayeth the BDMA.

But is this actually true in all cases?

Certainly, it’s true for a specific subset of the drug-using population, those who come to medical attention because they run into complications, can’t quit on their own, relapse frequently, or even die of their addiction.

Addiction ExpertsTM spend most, if not all, of their time looking after this very needy and generally noncompliant cohort, so I have no doubt that to them addiction does look like a chronic, progressive, relapsing, potentially fatal disease.

Coroners, by definition, don’t see the living, but they do see the fatal overdoses, so to them substance use and addictions look like fatal diseases. By definition, 100% of the overdose deaths that they see occur in people who were alive and used drugs.

Addiction ExpertsTM and Coroners are like two blind men groping around different parts of the elephant, each right and wrong in their own ways. Not surprisingly, given their limited perspectives, their conclusions and recommendations can be nihilistic, radical, and sometimes counterproductive.

“No one wants drug users to fail to take positive actions because they falsely believe their drug use is not controllable.” Gene M. Heyman

What we know and what we don’t know…

So, while it’s true that substance use can result in addiction or death, you won’t understand it if you only study the “worst of the worst”, those with “end stage” disease, or those who overdose. As with any health condition, you must look at the big picture.

When it comes to psychoactive substance use, the entire grown-up population is “at risk”, and that’s a lot of people! Once individuals reach the age where they start making decisions for themselves, we know that they make choices about whether they’ll use psychoactive substances, but we really don’t know how individuals balance the anticipated benefits with the risks.

“In sum, addictive drugs offer an immediate, reliable source of pleasure and escape. Their costs come later or not at all.” Gene M. Heyman

We know that psychoactive substances are available, some more so than others. We can estimate the supply for the legal substances but can only guess for the illegal ones.

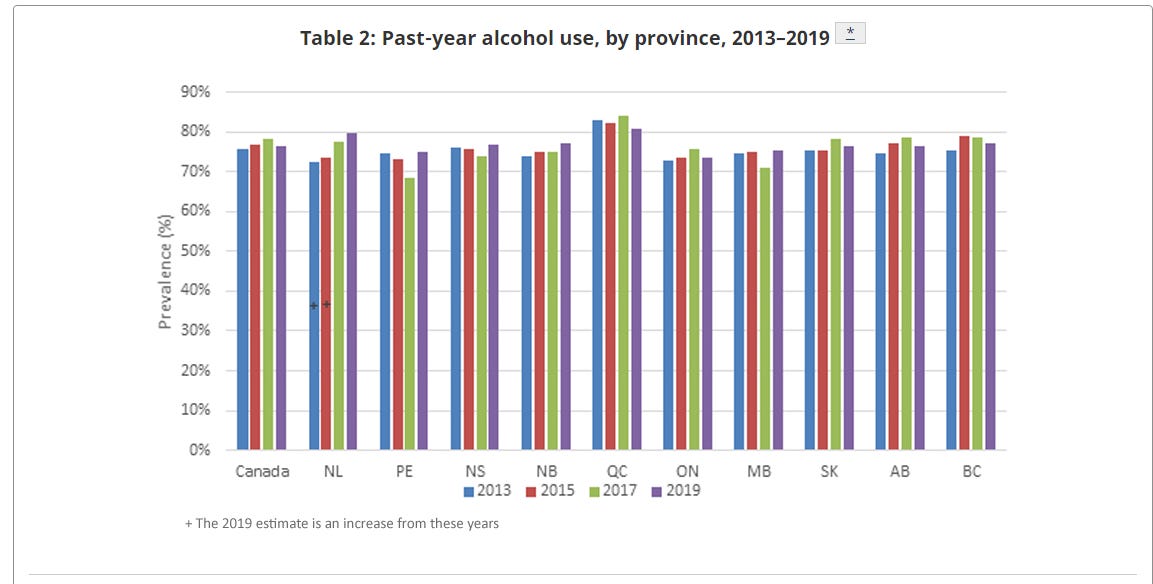

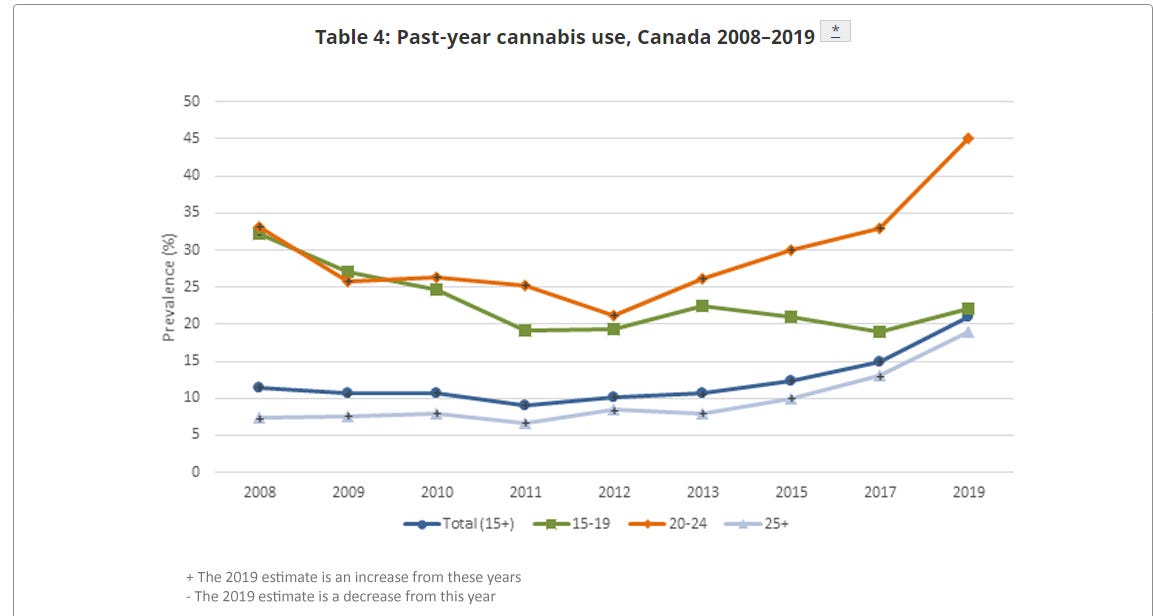

We know roughly how many people report using psychoactive substances. For alcohol, it’s 3/4 of the adult population! For cannabis, it’s over 20%! We don’t really know how many people fall into the various patterns of use (casual, binge, daily, etc.)

We know that some jurisdictions seem to have a bigger drug problem than others. For example, British Columbia and Alberta, with 1/4 of Canada’s population, account for over half of Canada’s overdose deaths, while Canada’s overdose death rate is triple that of England and Wales. The ExpertsTM claim that they really don’t know why. However, we also know that there’s far more fentanyl in the illicit drug supply in BC, together with a more “relaxed” attitude to enforcing the laws concerning opioid trafficking, production, and distribution. The Report for the Stanford Network on Addiction Policy tells us:

“Crime incident data confirms BC is the epicentre of drug-crime in Canada, reporting 57 opioid-related incidents per 100,000 population, compared to 13 per 100,000 in Alberta.”

“Despite the high volume of drug violations in BC, criminal charges for these offences are low, and appear disconnected from incident rates.”

We know the situation across North America got worse in the past three decades, and the Stanford-Lancet Commission told us why.

“The North American crisis emerged when insufficient regulation of the pharmaceutical and health-care industries enabled a profit-driven quadrupling of opioid prescribing. This prescribing involved a departure from long-established practice norms that prevailed before the mid-1990s—particularly in the expanded prescribing of extremely potent opioids for a broad range of chronic, non-cancer pain conditions. Hundreds of thousands of individuals have fatally overdosed on prescription opioids, and millions more have become addicted to opioids or have been harmed in other ways, either as a result of their own opioid use or someone else's (e.g. disability, family breakdown, crime, unemployment, bereavement). In response to the large pool of people who became addicted to prescription opioids, heroin markets expanded, which further increased morbidity and mortality. As heroin markets became saturated with illicit synthetic opioids, such as fentanyl, an already dire situation became a public health catastrophe, which has only worsened since the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic.”

We know that some people are more “at risk” for addictions than others. For example, there’s some evidence that addictions run in families, which could reflect genetics, the environment, or both. However, we can’t predict which individuals will become addicts, nor do we know why some people develop addictions and others don’t.

“One of the arguments in favor of the brain-disease model is that “no one chooses to be an addict.” With a few exceptions, this is true…. Rather, addiction emerges as a function of a series of choices, not one of which is the decision to be an addict. For example, a novice smoker becomes an addicted smoker one cigarette at a time. Conversely, one day of not smoking does not turn a current smoker into an ex-smoker. Many outcomes in life are a function of a series of small choices, rather than of just one momentous decision” Gene M. Heyman

We know that the clinical course of an addiction is highly individual, depending on many factors, including the age at onset, the intensity and duration of the substance use, the frequency and duration of remission and relapse, the medical and psychiatric status of the patient, the presence or absence of family help, and the availability of community or health system resources. The BDMA tells us that addiction is a compulsion (an “irresistible urge”), but there’s a fair bit of volition involved.

“Although popular opinion views addicts as impulsive, regular heavy drug use requires planning and, under most circumstances, subterfuge. Illegal drugs are not freely available, which means that addicts typically face a variety of hurdles to maintain a regular habit. Legal drugs are easier to obtain, but, as with illegal drugs, they often need to be used secretly in order to avoid sanctions from friends, family, and coworkers. Secrecy and getting around hurdles require purposeful, planful action.” Gene M. Heyman

We really don’t know how many people with addictions manage to quit, or how they do it. We’ve known for decades that some people who report past problems with substance use no longer have a problem, even though they were never formally “treated”, a phenomenon known as “maturing out”. Others seek medical care, while still others use peer support programs like Alcoholics Anonymous or Narcotics Anonymous.

We can name people like Elton John, Keith Richards, and Eric Clapton, who all had addictions and then went on to lead long and productive lives, presumably drug free, but we don’t always know what treatment they had. On the other hand, we know of people who died prematurely, like Jimi Hendrix or Janis Joplin.

Addiction ExpertsTM believe that opioid agonist therapy (OAT), such as methadone, is the preferred treatment for opioid addicts. In their view, nothing else works, which is true, probably because they only see the people for whom nothing else has worked. However, the quality of the evidence for OAT is poor, and we don’t have long term data to show what happens when addicts cycle in and out of their treatment program, which is a common pattern.5

“Trials evaluating OATs… suffer from poor methodological quality. A combination of small sample size, poor design, highly stringent eligibility criteria, effect estimates with tremendous imprecision, short-follow up time, missing data, and a major lack of consensus over patient important outcomes has led to an accumulation of a large yet very weak body of evidence. Whether it be illicit opioid use or risky behavior, the large number of definitions and measurements used to assess the same attribute suggest the need for more consensus in the field and understanding of what treatment outcomes are most important to addiction patients.” Brittany B. Dennis

We know there are many different possible trajectories of drug use, so it’s highly unlikely that everyone would respond to the same treatment. It’s a highly complex problem, and there’s no simple solution. We honestly don’t know the success rates for the various approaches, in part because individual addicts are so unique, but we do know that each method produces some successes and some failures. Because we don’t know much about the patient and program factors that make some treatments successful and others unsuccessful, there’s certainly a role for personal choice.

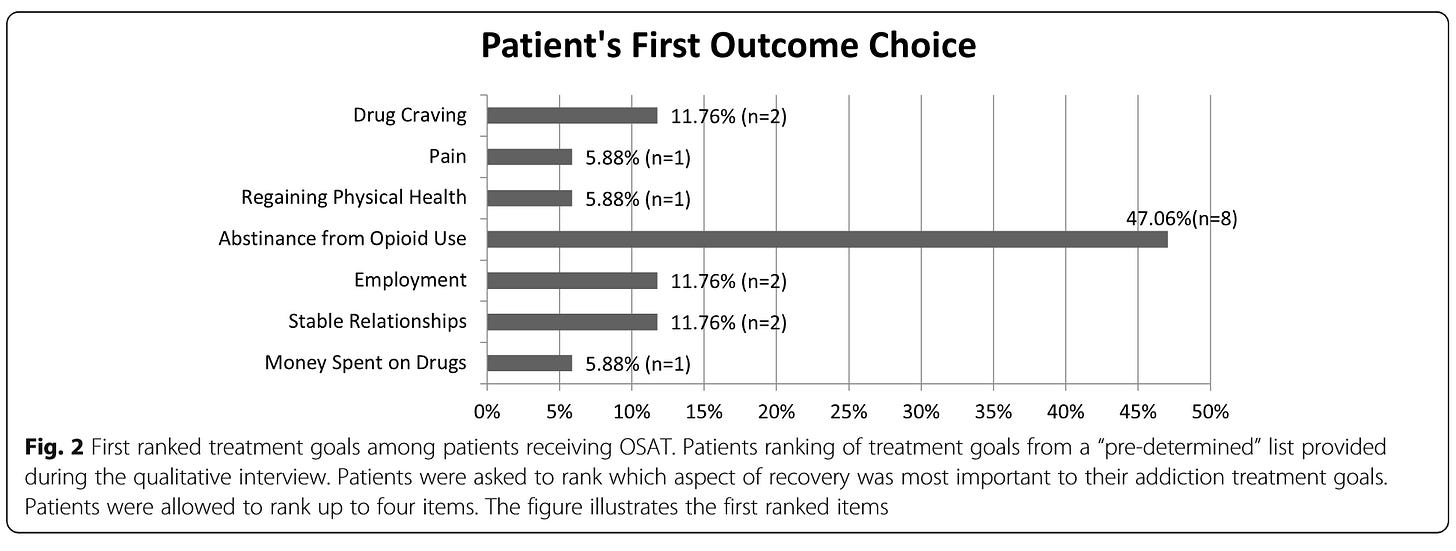

Often, the measures of “success” for treatment programs are “population based” measures (like overdose rates) or “program based” (like patient retention) rather than “patient based” (like reconnection with friends, employment, housing, etc.).

“Opioid use, measured by urine drug screens (UDS), and retention in treatment are the most commonly used primary outcomes measured in clinical studies and treatment programmes; however, it is unknown how well these outcomes are associated with patients’ goals in treatment. Personal and social functioning outcomes are, in contrast, much less commonly assessed.” Tea Rosic

We know that some (but not all) treated patients relapse. Whie the traditional wisdom suggests that addiction involves an endless series of failed attempts to quit, there is research showing that “… in a large group of individuals who recovered from drug addiction, the vast majority of individuals required five or fewer serious attempts and the most common pathway was one serious recovery attempt. These are much more modest numbers than might be expected for a chronic relapsing condition.”

“Importantly, this is not simply a matter of semantics, as a definition of addiction as a chronic relapsing disorder may actually have iatrogenic effects…. it is entirely plausible that the definition’s dire fatalism could actually undermine an individual’s motivation. Instillation of hope and positive expectations about treatment efficacy are established common factors for benefit from psychological treatments and the definition of addiction as a chronic relapsing condition may well reduce hope and diminish a person’s expectation that recovery is possible.” James MacKillop

The BDMA tells us that functional MRI scans show brain changes in people with addictions, but we don’t know if those changes are reversible. We don’t do those scans on everybody, so we don’t really know whether those changes occur ONLY in patients with addictions, or even whether EVERY addict has those changes. We don’t know whether OAT improves or aggravates the brain changes, but it’s hard to imagine how giving opioids could “fix” opioid-induced brain damage,. It’s even possible that OAT could cause other problems.

“A recent comparative cohort study indeed noted that individuals under [OAT] showed falls in cognitive performance, and changes in social perception, emotional interpretation and comprehension when compared to healthy subjects and abstinent subjects. Further research… is needed in this field.” Paolo Di Patrizio

We know that some substance users will overdose, but we can’t predict who, when or where that will occur. Not everyone who overdoses is an addict, some are casual users. Further, not all addicts will overdose, despite years of living at risk. Public Health ExpertsTM and Addiction ExpertsTM have pinned their hopes on overdose prevention policies involving population wide interventions, such as free drug testing, safer supply, safe consumption sites, the widespread availability of naloxone, and efforts to reduce stigma. However, we don’t know how many lives these interventions have saved, nor do we know whether these interventions actually encourage more people to use drugs, thinking that’s it’s now “safer” or “socially acceptable”. We need to look at the benefits AND the harms of any strategies we adopt. Besides that, we need to consider the feasibility. We can’t make all of these services available everywhere all the time, nor can we stop people from using drugs where and when they choose to.

Conclusion

There are a lot of gaps in our knowledge.

We need to know whether the things we’ve been doing are actually better than the alternatives.

We’ve put a lot of eggs in the OAT and/or safer supply basket, while setting aside many other strategies to help those with addictions. OAT and safer supply both involve Big Pharma, who arguably contributed to the current opioid crisis through their promotion of opioids for chronic pain. Do we trust them to “fix” the problem they created? We need to look at the many other available options.

The diagnosis of addiction involves persistent involuntary excessive drug use despite adverse consequences. In assessing what works, we should look at the outcomes and objectives that matter to the individual patient, such as abstinence, or maybe even less harmful drug use, defined by the harms that matter to them personally.

Yes, we can measure population-wide overdose rates and try to reduce those. However, at the individual level most addicts won’t consider their addiction treatment to be a huge success if all they do is avoid an overdose.6

On a societal level, rather than implementing measures that prevent overdoses at the “micro” level (each user, each drug purchase, each opportunity to use drugs), perhaps we should look at the societal factors (drug availability, the “culture” of using psychoactive substances, the reluctance to enforce drug laws), taking into consideration the evidence of differences between different communities, provinces, and countries.

For addictions and for overdoses, understanding the entire natural history is obviously essential if we are hoping to develop and implement effective and efficient medical and public health interventions. There’s a lot of work to be done!

I realize that pregnancy isn’t a “disease”, but I will use disease language to make a few points about the importance of knowing the natural history of a health condition.

There are many health conditions which don’t “progress”. Cancers, for example, are thought to start off as small “pre-cancerous” lesions, some of which resolve before we even become aware that they exist (i.e. they “regress”). Of those that do become diagnosable cancers, some grow slowly (or not at all) and others quickly, which is to say that not all cancers “progress” and not all cancers will necessarily kill you. Two people with the same type and stage of cancer can have very different disease stories.

Or maybe I should say “people with uteruses”.

For the sake of brevity, I’ll talk about “addictions”, although addictions these days are more “properly” referred to as “Substance Use Disorders” (SUDs). Detailed diagnostic criteria for SUDs are published by the American Psychiatric Association in the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, which is currently in its Fifth Edition. The published criteria are ostensibly based on the scientific literature with contributions from more than 200 subject matter experts, with the final result reflecting a process of voting and negotiation. The current SUDs criteria involve having at least 2 of 13 different “symptoms”. For the mathematically inclined, that means hundreds of different permutations and combinations of symptoms all lead to the same diagnosis.

For example, OAT apparently reduces the risk of overdose while people are taking it, but the risk of overdose increases in the weeks after they stop OAT. If a non-compliant addict stops and starts OAT repeatedly, does their overdose risk over time increase or decrease?

I venture to say that most substance users, whether casual or addictive, don’t go into any given round of substance use thinking that there’s a serious risk of dying, so telling them that any given strategy will “prevent death” may not be terribly compelling. For example, every time you fly there’s a risk of dying in a plane crash, but I doubt that you would be impressed by any airline promising simply to get you to your destination alive!

Some good points here, Rick. I particularly liked your point, and your analogy, in footnote 6 : )

A number of years back I read *The Biology of Desire: Why Addiction is Not a Disease* (2016) by Marc Lewis. It's long enough ago that I don't remember an awful lot from it, except that it was thought-provoking and it impressed me at the time. Lewis is a neuroscientist who became addicted to heroin during his med school years. One of the things I took away from his book was something like what MacKillop says in your article, i.e., that defining addiction as "a chronic relapsing disorder may actually have iatrogenic effects…. it is entirely plausible that the definition’s dire fatalism could actually undermine an individual’s motivation."

Haven't seen anything recently from Marc Lewis (though I haven't looked exhaustively). Have you read him, and if so what did you think of his argument in *The Biology ...* ? I would imagine he got a lot of blowback to his book in 2016, and being close to retirement age, may have decided it was a good time to retire, I don't know.