Wishful thinking about addictions (part 2)

The origins of the Brain Disease Model of Addictions

In my previous post I talked about IF-THEN logic, my premise being that people these days often “forget” that the hypothesis is qualified by an “IF”, while proceeding to state the conclusion (the “THEN”) as if it is categorically and indisputably true.

For example, Health Canada makes the claim that “Safer supply services …help prevent overdoses and can connect people to other health and social services”. They state their conclusion as a fact even though “…the evidence base for safer supply services is still developing”, in part because they are running safer supply pilot projects (otherwise known as “experiments”) in various locations across the country. Their working hypothesis is that safer supply prevents overdoses and connects people to health and social services, and they should say that that “IF the evidence supports that hypothesis THEN safer supply will be a preferred policy alternative”.

My previous post also summarized the Brain Disease Model of Addiction (BDMA), which dominates the current discourse about addictions.

To recap, proponents of the BDMA assert that addiction has been proven to be a biological disease of the brain with behavioural features. Therefore, as with any other disease (e.g. cancer), addicts should be free from stigma and blame, have access to the “sick role”, and receive sympathy, all while being supported to make their own decisions about their treatment.

In this post, I’ll look at the origins of the BDMA.

How did we get to this point?

The BDMA is generally credited to Alan Leshner, the former director of the US National Institute on Drug Abuse. In 1997, he wrote an influential editorial1 in the journal Science entitled “Addiction Is a Brain Disease, and It Matters”. Summarizing 20 years of scientific advances, Leshner asserted:

“Recognizing addiction as a chronic, relapsing brain disorder characterized by compulsive drug seeking and use can impact society’s overall health and social policy strategies and help diminish the health and social costs associated with drug abuse and addiction.”

In essence, he said “IF we recognize addiction as a brain disease AND we change our policies accordingly, THEN we should be able to reduce the health and social costs of addictions.” He left out the IF deliberately, in part because he believed that the science was settled, and in part because he wanted to challenge the prevailing “nonscientific”, moralizing, and stigmatizing attitudes to addiction.

He further developed his argument in a second article, similarly entitled “Addiction Is a Brain Disease”, published in Issues in Science and Technology in 2001.

Taking the two articles together, Leshner summarized the state of the art in addictions science at the time, and he laid out a multi-faceted future for addictions research, care and public policy. His thesis included a LOT of IF’s and THEN’s! Many things needed to happen between the recognition of addictions as a brain disease and seeing the benefits of the different approach!

Unfortunately, despite his detailed hypothesis, the one idea that took hold is the simplistic one found in the title, namely “Addiction Is a Brain Disease”. Few people bothered to read any further!

Building on that single thought, the BDMA has gone on to have a profound effect on the efforts of clinicians, policy makers, researchers, and research funders. It is stated as established scientific fact, rather than working hypothesis.

But what did Leshner actually say?

Bear with me as I go through Leshner’s working hypothesis in some detail. I think it’s informative to hear what the man said in his own words, such as:

“Understanding drug abuse and addiction in all their complexity demands that we rise above simplistic polarized thinking about drug issues. Addiction is both a public health and a public safety issue, not one or the other. We must deal with both the supply and the demand issues with equal vigor. Drug abuse and addiction are about both biology and behavior. One can have a disease and not be a hapless victim of it.”

Addictions are a public health AND a public safety issue!

Previously, the working hypothesis had been that addiction was an individual moral failing and/or a character defect, prompting Leshner to observe that:

“…historic policy strategies focusing solely on the social or criminal justice aspects of drug use and addiction have been unsuccessful. They are missing at least half of the issue. IF the brain is the core of the problem, [THEN] attending to the brain needs to be a core part of the solution.”2

Get that? IF addiction is a brain disease, THEN dealing with the brain disease is PART of the solution, but not ALL of it! Treating it SOLELY as a social or criminal problem doesn’t work, but that’s not to say that you do nothing about the social and criminal aspects.

To that end, he said:

“Because addiction is such a complex and pervasive health issue, we must include in our overall strategies a committed public health approach, including extensive education and prevention efforts, treatment, and research.”

and

“…a public health approach to stemming an epidemic or spread of a disease always focuses comprehensively on the agent, the vector, and the host. In the case of drugs of abuse, the agent is the drug, the host is the abuser or addict, and the vector for transmitting the illness is clearly the drug suppliers and dealers that keep the agent flowing so readily. Prevention and treatment are the strategies to help protect the host. But just as we must deal with the flies and mosquitoes that spread infectious diseases, we must directly address all the vectors in the drug-supply system. In order to be truly effective, the blended public health/public safety approaches advocated here must be implemented at all levels of society–local, state, and national.”

In other words, even though addiction is a disease affecting the individual, any solution to the epidemic requires efforts to limit the supply of drugs by dealing with the drug vendors and manufacturers.3

Furthermore:

“Addiction begins with the voluntary behavior of drug use, and although genetic characteristics may predispose individuals to be more or less susceptible to becoming addicted, genes do not doom one to become an addict. This is one major reason why efforts to prevent drug use are so vital to any comprehensive strategy to deal with the nation’s drug problems. Initial drug use is a voluntary, and therefore preventable, behavior.”

Casual drug use is a risk factor for addictions, and it reflects the social milieu, including the availability of psychoactive substances and the prevailing attitudes about their use. Prevention is critically important! It includes primary prevention of addiction in those who are vulnerable, going well beyond the current “harm reduction” approach for established addicts, or the “safer supply” for those who are experimenting but not yet addicted!

The addictions experience is both personal and shared!

Unlike most (if not all) other diseases, addictions affect not just the individual but also “the public”.

My heart attack is mine. It’s not a public health crisis, even if fifty guys like me all have heart attacks in the same year. When it comes to heart attacks, effective treatment can and should focus on the individuals and their hearts.

My addiction, on the other hand, reflects the psychoactive substances available in my community together with my behaviour in response to those drugs. My addiction is a social problem affecting many others, not just me.

A comprehensive approach to addictions therefore addresses the drugs, the drug suppliers, the addicts, and their community.

As Leshner put it, the defining feature of addiction:

“…is virtually uncontrollable compulsive drug craving, seeking, and use that interferes with, if not destroys, an individual’s functioning in the family and in society.”

and

“Compulsive craving that overwhelms all other motivations is the root cause of the massive health and social problems associated with drug addiction. In updating our national discourse on drug abuse, we should keep in mind this simple definition: Addiction is a brain disease expressed in the form of compulsive behavior. Both developing and recovering from it depend on biology, behavior, and social context.”

Getting addicted is a process!

As for how individuals get addicted, Leshner said:

“Although each drug that has been studied has some idiosyncratic mechanisms of action, virtually all drugs of abuse have common effects, either directly or indirectly, on a single pathway deep within the brain. This pathway, the mesolimbic reward system, extends from the ventral tegmentum to the nucleus accumbens, with projections to areas such as the limbic system and the orbitofrontal cortex. Activation of this system appears to be a common element in what keeps drug users taking drugs. This activity is not unique to any one drug; all addictive substances affect this circuit.”

That bears repeating! It was understood nearly three decades ago that ALL addictive substances affect pretty much the same brain circuitry, at least when it comes to getting addicted! That makes me wonder whether the treatments for addictions should bear some commonality, regardless of the specific substance involved. Maybe what we’ve learned in treating alcoholism could inform our approach to opioid addictions?

Leshner notes that addictions start with voluntary behaviour and evolve over time, stating:

“What may make addiction seem unique among brain diseases, however, is that it does begin with a clearly voluntary behavior – the initial decision to use drugs. Moreover, not everyone who ever uses drugs goes on to become addicted. Individuals differ substantially in how easily and quickly they become addicted and in their preferences for particular substances. Consistent with the biobehavioral nature of addiction, these individual differences result from a combination of environmental and biological, particularly genetic, factors.”

and

“…drug addiction is a brain disease that develops over time as a result of the initially voluntary behavior of using drugs.”

Unlike other brain diseases, like Parkinsonism, addiction builds on voluntary behaviour.4 That being so, addicts are NOT simply unfortunate victims of their disease, in the way that someone with Parkinsonism would be. As Leshner said:

“…the recognition that addiction is a brain disease does not mean that the addict is simply a hapless victim. Addiction begins with the voluntary behavior of using drugs, and addicts must participate in and take some significant responsibility for their recovery.”

Furthermore, the acute and chronic brain changes seen in addictions are the result, not the cause, of drug use:

“Using drugs repeatedly over time changes brain structure and function in fundamental and long-lasting ways that can persist long after the individual stops using them.”

While only some psychoactive substance users become addicted:

“Clinical observation and more formal research studies support the view that, once addicted, the individual has moved into a different state of being. It is as if a threshold has been crossed.”

Unfortunately, being a neuroscientist, Leshner considered that threshold to be a “metaphorical switch” with a biological basis, leading to his view (see below) that there could be a biological treatment.

On the role of the addict in their treatment

As with any disease, addicts have a role to play in their own recovery, accepting that their addictive behaviors might make that more complicated. Leshner said:

“…having this brain disease does not absolve the addict of responsibility for his or her behavior, but it does explain why an addict cannot simply stop using drugs by sheer force of will alone.”

and

“Moreover, as with any illness, behavior becomes a critical part of recovery. At a minimum, one must comply with the treatment regimen, which is harder than it sounds.”

Setting goals for addiction treatment

Noting that the “essence of addiction” is “compulsive drug seeking and use, even in the face of negative health and social consequences”, Leshner said:

“These are the characteristics that ultimately matter most to the patient and are where treatment efforts should be directed. These behaviors are also the elements responsible for the massive health and social problems that drug addiction brings in its wake.”

and

“…a good treatment outcome, and the most reasonable expectation, is a significant decrease in drug use and long periods of abstinence, with only occasional relapses. That makes a reasonable standard for treatment success—as is the case for other chronic illnesses—the management of the illness, not a cure.”

However, he observed that:

“Although some addicts do gain full control over their drug use after a single treatment episode, many have relapses. Repeated treatments become necessary to increase the intervals between and diminish the intensity of relapses, until the individual achieves abstinence.”

and

“Very few people appear able to successfully return to occasional use after having been truly addicted”

Realistically speaking, then, the “outcomes that matter” to the addict and their social group are REDUCED DRUG SEEKING and REDUCED DRUG USE, LONGER PERIODS OF ABSTINENCE, and ONLY OCCASIONAL RELAPSES.

The ultimate goal of treatment is ABSTINENCE, period.

The nature of treatment

Regarding treatment, Leshner observed that:

“People often assume that because addiction begins with a voluntary behavior and is expressed in the form of excess behavior, people should just be able to quit by force of will alone. However, it is essential to understand when dealing with addicts that we are dealing with individuals whose brains have been altered by drug use. They need drug addiction treatment.”

In his view, that treatment would not be purely “biological”:

“These goals can be accomplished through either medications or behavioral treatments (behavioral treatments have been successful in altering brain function in other psychobiological disorders).”

and so:

“If we understand addiction as a prototypical psychobiological illness, with critical biological, behavioral, and social-context components, our treatment strategies must include biological, behavioral, and social-context elements. Not only must the underlying brain disease be treated, but the behavioral and social cue components must also be addressed.”

YES! Addiction treatment must be multi-faceted. It’s not just medications to fix the broken brain circuits. You have to address the behaviours of the addict and their social context, or they’ll relapse.

Sadly, however, Leshner undercut his own argument by saying:

“Elucidation of the biology underlying the metaphorical switch is key to the development of more effective treatments, particularly antiaddiction medications.”

thereby setting the stage for years of research looking for drugs to “fix” addictions.

In summary…

Leshner’s article was written nearly 30 years ago, based on over 20 years of preceding research.

What he said was fairly well balanced, with a couple of minor blips. What ensued was unhinged.

Labelling addictions as a brain disease (as per the title of Leshner’s articles) led clinicians, policy makers, researchers and research funders on a single-minded quest to find the underlying brain lesion and the drug to fix it, an overly simplistic biological fix for a problem that is clearly much more complex!

Despite the search for the brain switch that triggers addictions and the drugs to reset that switch, there hasn’t been a lot of progress. (You’ll have to trust me for now, but I will review this in future posts.)

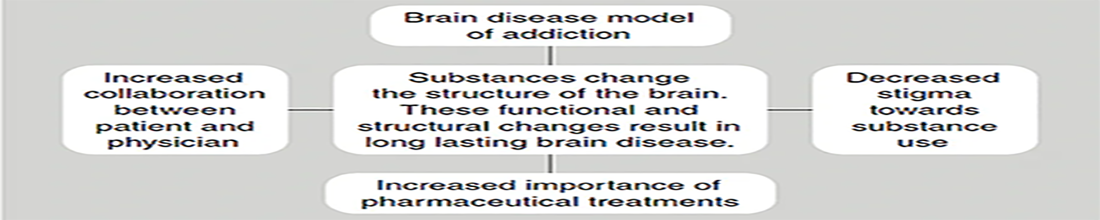

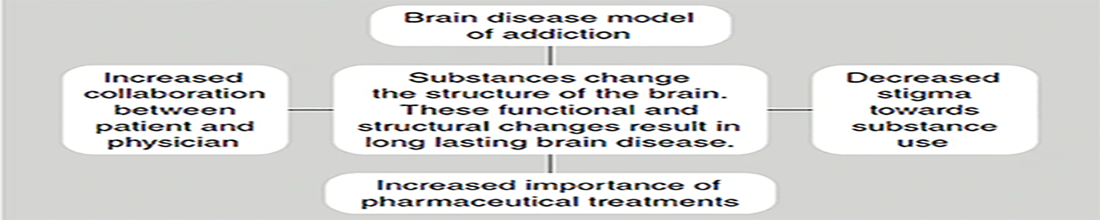

The following graphic, taken from an article in the Psychiatric Times, confirms the current narrow-minded focus on biology in the BDMA. Note, in particular, the emphasis on decreased stigma and the “increased importance of pharmaceutical treatments”, and the relative absence of any behavioural treatments or measures to address the social context of the addict.

It doesn’t have to be this way! At this point we have FIVE DECADES of experience telling us that:

ALL of the above generally applies to ALL addictions.

What we’ve learned about one addictive substance should guide our efforts with others.

In treating the addict, you’ll have to consider their biology, their behaviour, and their environment. Simplistic solutions won’t work.

There’s a role for primary prevention of addictions, reducing or eliminating the casual use of psychoactive substances and limiting their availability.

Success in addictions treatment should be measured by REDUCTIONS IN DRUG SEEKING, DRUG USE, and RELAPSES, together with LONG PERIODS OF ABSTINENCE. The ultimate (but difficult to achieve) goal is ABSTINENCE.

Personally, I find it disheartening to think that we’ve “known” these things for decades, and yet we’ve lost the plot.

Our public policies for psychoactive substances are all over the map. The clinical approach to alcoholism is radically different from the approach to opioid addiction - alcoholics are urged to abstain, while opioid addicts are offered replacement opioids! Our public health people agonize about the harms of minimal social alcohol consumption while supplying free opioids through safer supply. We print warnings on cigarettes because it’s harmful to smoke them and yet we offer free testing for illicit street drugs, not because they are harmful (which they are!), but because they might not be what you thought you were buying. And the litany of insanity goes on!

Those who disagree with all this nonsense have a hard time getting their voices heard, but they are out there.

“It should go without saying that the debate about whether or not addiction is best seen as a chronic, relapsing brain disease should eventually be decided, or at least strongly influenced, by evidence and reasoned debate. Tactics used by supporters of the BDMA are sometimes inimical to this aspiration. It does no good to avoid proper scientific debate by claiming that the issue has already been decided or by implying that raising doubts about the validity of the BDMA is always irresponsible and inevitably dangerous to the health and welfare of persons labelled as addicts.”

I’ll continue to explore these matters in an upcoming post (or posts).

Now cited over 2500 times!

I added the [THEN], for clarity, because he was making an IF-THEN argument.

Both legal and illegal, I might suggest!

Leshner asserts that “voluntary behavior patterns are, of course, involved in the etiology and progression of many other illnesses, albeit not all brain diseases. Examples abound, including hypertension, arteriosclerosis and other cardiovascular diseases, diabetes, and forms of cancer in which the onset is heavily influenced by the individual’s eating, exercise, smoking, and other behaviors.” I don’t think this analogy is perfect. One might argue that overeating is voluntary and that it leads to obesity, which in turn is a risk factor for diabetes. However, the diagnosis of diabetes is NOT based on a compulsion to overeat - diabetes is a different problem which can occur in the absence of overeating. In addictions, however, voluntary casual drug use evolves, for some, into an addiction, the hallmark of which is compulsive drug use.

Really enjoyed this Rick. Thanks.

I think many people are noticing that many human habits and failings are being redefined as "addictions" now in modern victimhood society. Much easier for one to say he is a porn addict, drug addict, food addict, internet addict, sugar addict, video game addict, whatever than to actually take responsibility for moderating his own behaviour.

It is interesting that every behaviour that creates positive feedback (especially immediate positive feedback) "wears a groove" in the brain, using the same dopamine-reward system. As some people know I was very into exercise and racing for several decades and can honestly say that I got edgy, cranky and shaky if I went for more than 24 hours without a good workout. Does this mean I was "addicted"? I'm sure someone could have done an fMRI and see the functional/structural changes my "ingrained habit" had caused.

This actually dissolves into a deeper issue. What is "me". We have a conscious brain and an unconscious one. If we were simple creatures nobody would be fat and everyone would be fit and go to the gym for an hour a day, probably at 530AM. But humans are complex creatures, and "I" don't have totaly control over "me".

That said, the idea that "I" have no control over "me" is toxic, dangerous, negates the idea of free will and creates an anarchic society where nobody owes anyone anything because none of us are actually able to control ourselves.

My favourite summary of this issue is the one-liner, that I think would be great for a t-shirt: "My Brain Made me Do It".

All true. However one thing that is seldom discussed is our underlying inherent need to experience altered states of consciousness. These can be both constructive (daydreaming, meditation) or destructive (substance initiated in some contexts). Also, there are 2 main types of use which are often left unrecognized. 1. Recreation 2. Self-medication. Understanding the “why” of use is very important to mount an effective treatment strategy. Self-medicating use is much harder to treat as there is always either a trauma or an underlying mental illness in the background that also needs to be addressed.