“…the word ‘disease’ is in general use without formal definition, most of those using it allowing themselves the comfortable delusion that everyone knows what it means.”

Dr. J.G. Scadding, Professor of Medicine, University of London, 1967

In my previous post I described the somewhat idealistic reasoning process through which diseases and their cures are “discovered”:

Clinicians recognize a “syndrome”, a cluster of symptoms shared by a group of patients.

The syndrome description is then fleshed out through the inclusion of “typical” findings on physical examination (signs), and later by the results of blood tests, x-rays, biopsies, etc.

Once there’s some consistency, the specific grouping of symptoms, signs and test results is translated into diagnostic “criteria” describing a specific “disease”. This can involve both inclusion and exclusion criteria.

This allows “like” patients to be grouped together and separated from “unlike” patients, facilitating both clinical care and research.

Through observation over time, we learn the “natural history” of the disease, including the time course, possible outcomes, complications, etc.

Research eventually reveals the root cause (the “etiology”) and the mechanisms of the disease (the “pathophysiology”).

Knowing these, a remedy can be developed, ideally one which works specifically on the cause of the problem, improving the outcome while avoiding side effects.

For health care systems (i.e. when organizing care for groups of patients), clinically valid and useful disease categories:

are stable, meaning that different doctors in different places at different times will diagnose the same patients in the same way,

reliably distinguish the people with a disease from those without that disease, and from those with other diseases,

fully explain the clinical needs of the patients during their illness,

guide decisions about their treatments, and

predict their response to treatment, including how many will recover (or not).

With this knowledge, at least in theory, the people who run our health care systems can figure out how many patients will require services, what services they’ll need, how many staff will be needed, and what drugs and other treatments will be required. For example, where I live, the folks who run our renal dialysis programs track province-wide data so they know how many people have advancing renal failure and where they live, so they’ll know where to set up dialysis units.1

For health care research, clinically valid and useful categories also allow researchers to develop “testable” theories about the disease, informing research into the cause and treatments.

However…

All the above reflects the “realist” or “biomedical” model, in which your disease reflects a clear deviation from your normal bodily structure and function, a uniquely personal experience linking your symptoms with the objective abnormalities on your physical examination and/or various tests. For any given disease, you either have it or you don’t. (You can’t have “a little bit” of cancer, for example.)

By this logic, the causes of your disease are also “personal”, reflecting your specific bodily response to your social, cultural, and environmental milieu. Exposure to bacteria can give you pneumonia, depending on your lung health and immune response. Exposure to cigarette smoke or pollution can give you lung cancer, depending on your genetic makeup and other factors.

Any treatment, therefore, will be designed for and individually delivered to you, the person with the disease. This usually involves “fixing” you, using drugs, devices, or other medical interventions like physical therapy, dietary changes, etc..2

For example, Major Depressive Disorder is described as a mental disorder caused by chemical imbalances in the brain, with some people being more susceptible based on their genetics and upbringing. Your parentage and the way you were raised aren’t fixable after the fact, so, if you’re depressed, your treatment might include:

psychotherapy (such as Cognitive Behavioural Therapy, which “…helps a person to recognize distorted/negative thinking with the goal of changing thoughts and behaviors to respond to challenges in a more positive manner”),

antidepressants (to rebalance your brain chemistry),

electroconvulsive therapy (to “reboot” your brain), and

general personal care (such as self-help interventions, regular exercise, careful attention to sleep patterns, eating well and avoiding alcohol)3.

In other words, even though your depression might be a reasonable emotional response to your current depressing life circumstances (which in turn might be a result of your genetics and upbringing), the primary objective of your treatment is to “fix” your brain (presumably with the hope that you’ll then be able to get yourself out of the mess you are in).

Yes, I’m exaggerating a bit! Some doctors will help you to identify the problems in your life and then make the necessary changes. However, in all probability your medical insurance will fund your drugs and maybe a short course of psychotherapy, but not the costs of your divorce or job retraining. Your sick leave will cover the time it takes to get started on medication, but not the time it takes to sort out your life.

In short, the biomedical way of thinking has its limitations, one being that we focus too much on the disease inside the person and not enough on the person hosting the disease.

We do occasionally give a passing nod to environmental factors, things like improved sanitation for cholera or improved air quality for asthma, but sadly that’s more the exception than the rule. And, when you think about it, even “public” health measures designed to benefit the entire population, things like vaccinations or “masking”, are still implemented one person at a time.4

…and there are other problems!

For many diseases5, we haven’t really nailed down the etiology and the pathophysiology. We often have a theory, presented as “fact”, but in many cases it’s either unproven or totally wrong.

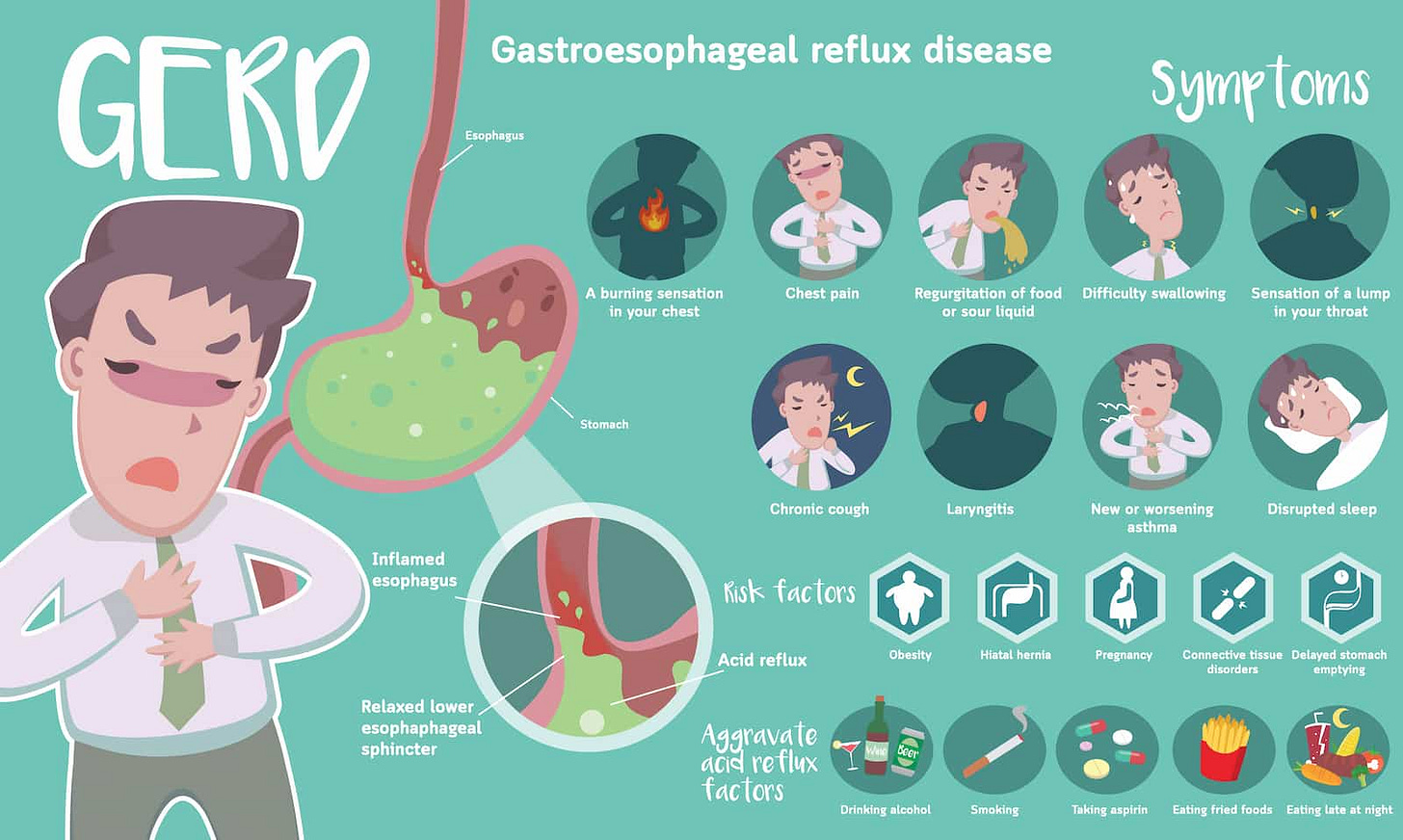

Consider indigestion, burping, heartburn, and dyspepsia, all of which have plagued humanity forever. Their remedies take up a lot of shelf space in pharmacies, which tells us that they are common, possibly universal6. Once Big Pharma discovered some drugs that reduce the production of acid in your stomach, heartburn was rebranded as “gastroesophageal reflux disease” (GERD). In theory, GERD results from regurgitation of acidic stomach contents into your esophagus, which means that we should find evidence of acid in your esophagus, and/or the lining of your esophagus should look “burned”. However, as it turns out, indigestion, burping, heartburn, and dyspepsia don’t correlate very well with any of the various tests, including endoscopy7, esophageal acidity measurements, etc.. You can have obvious reflux when we look down your esophagus and yet have no symptoms at all. Conversely, you can have terrible heartburn with totally normal tests. There’s no combination of symptoms, signs and test results that reliably separates those with GERD from those without, and either way we don’t have a good explanation. The treatment for indigestion is the same as for GERD, namely overpriced medications with worrisome side effects8 which may or may not work.

Even when we know the root cause and the pathophysiology, there are times when advances in technology lead us to earlier diagnosis, meaning that we must redefine the diagnostic criteria, relearn the natural history, and rethink the necessity for treatment.

Pneumonia, for example, used to be a clinical diagnosis, based on symptoms of fever and cough together with certain abnormal findings on physical examination9. When xrays came along, it became obvious that some people had pneumonia without the fever, cough, or abnormal examination. Then CAT scans came along, and we found there were some more pneumonias that you couldn’t see on the plain chest xrays. Any knowledge we had about the natural history and treatment of pneumonia was based on the ones diagnosed clinically, with no guarantee that the ones seen only on xray or on CAT scan would behave the same. Many of those previously unrecognized pneumonias might have resolved without treatment, while others, left untreated, would eventually become clinically obvious. Not knowing which pneumonias fall into each category, I suspect that we still treat the majority with antibiotics, which might well be more than is necessary.

On the other hand, early detection is the basis of screening programs, in which we actively go looking for a disease before any symptoms appear, hoping that the disease will be more easily treatable or even curable in its “early” stages. This is the rationale for doing mammography to detect breast cancer, for example. However, in doing so, we sometimes find “false positive results”, abnormalities that lead to further investigations (and sometimes other diagnostic labels) but no diagnosis of breast cancer. This is not a trivial problem; “half of all women experience false positive mammograms after 10 years of annual screening.”

Wow! There are way more diseases and sick people than we ever imagined!

As time goes on, more and more of life’s problems are being defined and treated as diseases, a process referred to as “medicalization”. It follows that the number of “diseased” people is steadily increasing.10 Health Canada, for instance, tells us that “45.1% of Canadians lived with at least one major chronic disease in 2021”!11

Some blame the medical profession for this, thinking that doctors want to expand their target market and/or take control of everything. However, other groups contribute.

Government can play a role, through policies targeting certain diseases or treatments. Canada’s Low-Risk Alcohol Drinking Guidelines, for example, recommend consuming two or less standard drinks per week! Further communications aimed at physicians suggest that doctors screen all patients for excess alcohol use, effectively medicalizing any amount of alcohol consumption.12

The pharmaceutical industry plays an obvious role. Any number of diseases have been tailor-made to create new markets for new drugs. Consider “erectile dysfunction” (ED), which sprang into prominence after sildenafil (which failed as a treatment for pulmonary hypertension) was found to have some interesting and marketable sexual side effects.

The biotechnology industry do their part. The people who make endoscopy devices, for example, have often made undisclosed payments to the authors of the clinical practice guidelines describing when and where endoscopy should be used.

Patients themselves sometimes see medicalization as a means to have their illness experiences and behaviours legitimized by medical science. For example, patient self-help groups demanded recognition of Chronic Fatigue Syndrome as a disease caused by objective pathological processes (which, by the way, have never been confirmed).

And, of course, there are plenty of other interested parties, including nurses, dieticians, physiotherapists, pharmacists, health care organizations, and the media.

I’m not “bad”, I’m “sick”!

Leaving aside the question of who causes it, the process of “medicalization” recognizes that disease, illness and sickness (or the sick role) are not purely biological. They are also social constructs, so values play a role.

Behaviours reflect mental functions. Historically, some behaviours were considered “moral badness”, to be dealt with by the person, their church, their family, and/or the criminal justice system. Increasingly, problematic behaviours are being reframed as “sickness”, transferring responsibility to the health care system. Practically speaking, this means that:

“deviants” receive partial absolution from moral responsibility for their actions (because they reflect a disease process, not personal choice),

the diseased are afforded the sick role (and sometimes “destigmatized”, depending on the disease13), somewhat conditional on their willingness to accept medical advice and treatment, and

“treatment” is (perhaps optimistically) seen to be more effective than punishment.

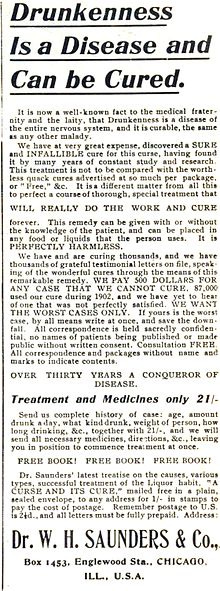

Alcoholism, for example, was once considered a moral failing. The American Medical Association (AMA) officially reclassified it as a disease in 1956, taking it from being a behavioural problem (the product of bad choices) to being a chronic brain disorder (something medically “treatable”, while still requiring a lot of patient participation). The exact nature of that postulated brain disorder wasn’t known then and it still isn’t.14 With no clear understanding of the cause, alcoholism remains one of the most severe and prevalent mental disorders. Some of the most effective treatments are the non-medical ones, including abstinence and 12-step programs. However, moving alcoholism into the medical domain hasn’t taken it out of the legal realm. There are plenty of laws about who can make alcohol, where it’s sold, who can drink it, where they can drink it, and what they can or cannot do when drinking (i.e. driving). Clearly, defining alcoholism as a disease hasn’t removed all personal responsibility for drinking-related behaviour, and there is still a stigma associated with the diagnosis.

Similarly, drug addiction is also labelled as a disease over which the addict has little or no control, hence the move to decriminalize many of the associated behaviours. As with alcoholism, the underlying brain disorder is really not understood, the treatments are not particularly effective, and much of the stigma remains.

However, the reclassification of behaviours isn’t a one-way street, depending on societal perspectives. Homosexuality, for example, once considered to be a disease, was “demedicalized” by the American Psychiatric Association in the early 1970s, in response to lobbying by the gay liberation movement. It is now seen in many countries as neither disease nor deviance, but as a reflection of the normal range of human sexual behaviour.

You might think you’re healthy, but you probably aren’t.

The World Health Organization defines health as “a state of complete physical, mental and social well-being”, which opens the door to all sorts of physical, mental, and social issues (like poverty or homelessness) being treated as health problems, if not actual diseases.

In Canada, for example, self-rated mental “health” declined to 59.0% in 2021, leaving 41% of the population mentally unwell. In modern society, mental distress is increasingly seen to reflect an increasing prevalence of treatable psychiatric diseases.

Highlighting the magnitude of the overall problem, the International Classification of Diseases (ICD), now in its 11th iteration, lists about 80,000 items, among which you will find:

diseases that have no symptoms, showing up only on examination or through testing (like solitary cysts in the kidney),

things that aren’t problematic in and of themselves, but increase your risk of another disease down the road (like high blood pressure or elevated cholesterol, both of which increase your chance of a heart attack),

diseases that don’t affect longevity (like thyroid cysts),

fatal diseases with no cure (like ALS),

things that were once considered part of aging but are now diseases (like male-pattern baldness, erectile dysfunction, etc.),

solitary symptoms for which there’s no explanation (like that sore back you had the other day),

symptom groupings (or “syndromes”) for which there are no objective abnormalities on examination or testing (e.g. chronic fatigue syndrome),

conditions for which the basic cause is honestly unknown (despite the “working theory”, like GERD),

newly recognized syndromes which haven’t been known long enough for us to understand the natural history (like “long COVID”), and

the list goes on!

Many of these really don’t fit the biomedical model of disease, although you will usually find that somebody has imaginatively tried to “retrofit” the diagnosis to an explanation.

So, what’s the problem?

Obesity provides a great example of medicalization and the tension between societal norms, behaviours, stigma, disease, and the availability of medical treatment.

Being big was once thought to be the result of poor food choices, too much food, too much television, insufficient physical activity, and too little sleep, which are all lifestyle choices. Obesity rates in Canada have soared over the past few decades, with 30% of the population now considered obese and another 35% overweight. You might wonder why 2/3 of the population changed their habits, perhaps it was a brain virus?15

Obesity is a risk factor for bad outcomes, although to be obese doesn’t guarantee that you’ll die early.

There’s been no shortage of remedies over the years, anything from Weight Watchers to hypnosis to amphetamines (and other drugs) to bariatric surgery. Most don’t work well, over the long haul.

To be labelled (or diagnosed) obese is “stigmatizing”. Recent campaigns sought to “rebrand” bigness as “healthy”, paradoxically in parallel with a move to more clearly label obesity as a disease, both of which would absolve the individual from any personal responsibility for their condition.

Along comes semaglutide, which “interacts with the parts of the brain that suppress your appetite and signal you to feel full”,16 highlighting “…the value of treating obesity as a chronic metabolic disease instead of expecting people to rely solely on willpower and lifestyle changes to manage their condition.” Tada, problem solved! Obesity is officially an individual disease, a brain disorder of sorts, and we have a cure, one which is “… approved to treat chronic weight management in the 70% of American adults who are obese or overweight”.

You don’t even have to rely on willpower and lifestyle changes! Just take the drug! In one move we let overweight individuals off the hook, we can leave the food industry alone, and Big Pharma has an expensive drug17 for 70% of the population, one they’ll need to take for life.

Isn’t medicalization grand?

On the other hand, it’s blatantly obvious that in many cases health data is NOT being used to plan ahead. If it was, we wouldn’t have the annual blitz of news articles telling us that the health care system is overwhelmed during “flu season”, which happens every year around the same time!

The “repair shop” model.

Of note, these general lifestyle measures form part of the management plan for virtually every diagnosis!

Sometimes with individual penalties for those who fail to comply!

Maybe even most diseases!

And the very fact that there are so many remedies also tells you that the remedies don’t really work!

Endoscopy involves looking directly into your esophagus with a flexible scope.

“In recent studies, researchers advised that PPIs should be used for the shortest time period at the smallest effective dose, as infections, impaired absorption of nutrients, dementia, kidney disease, and hypergastrinemia-related side effects are emerging as possible consequences of long-term use”. See reference.

Like dullness to percussion, crackling breath sounds in the lungs, and a host of other more obscure “signs” that we spent lots of time learning about in medical school and never encountered in real life. One example would be “Egophony”, a finding where consolidated, fluid-filled, or compressed lung decreases sound amplitude and only allows select frequencies to pass through, which changes the sound of the vowel “E” to "A."

Many who have a disease are not “sick” or “ill”. There are a lot of asymptomatic diseases, including things that don’t really impair function. One example would be “myopia” (short-sightedness), which is correctable with glasses or laser surgery and doesn’t cause disability (unless you want to be a commercial pilot).

This might leave you wondering how many people have “minor chronic diseases”!

These were developed by the Canadian Centre on Substance Use and Addiction, a supposedly non-governmental organization established by an Act of Parliament in 1988, reporting to Health Canada, with the Chair and up to four of the 13 board members appointed by the Governor General acting on the advice of the federal Cabinet. No, it doesn’t really sound “non-governmental”, does it? Mind you, for Income Tax purposes they set it up as a “charity” so they wouldn’t have to pay for it!

However, even when reclassified as “disease”, the stigma remains for health conditions affecting behaviour (like addictions), “blame-worthy” diseases (like the consequences of smoking), and certain infectious diseases (like STD’s).

The causes are sometimes listed as “biological factors, environmental factors, social factors and psychological factors”, which amounts to saying both everything and nothing.

It could be that the actual cause of the obesity epidemic is not the individual behaviour of 2/3 of the population, but rather the rise of ultra-processed foods. If so, then obesity is actually a mass poisoning. However, there’s a lot of money to be made selling ultra-processed food, and it would be hard to change the food industry. What’s more, there’s even more money to be made selling obesity drugs, so everybody wins!

Note the biomedical explanation, custom tailored to explain how this new drug works. What it doesn’t tell us is why those parts of the brain stopped working in so many people!