The problem with "medical necessity"

When you can't say what's necessary, consumerism and medicalization fill the void!

In my previous post, I suggested that we need to rethink the foundation of the Canadian health care system, the Canada Health Act (hereinafter referred to as “the Act”).

I believe that our health care system is a classic example of mission creep. We were never really clear about the ultimate purpose of our health care system. Without having clearly stated what we hoped to accomplish, we can never be sure that we’re going in the right direction, and we’ll never know whether (or when) we’ve succeeded. At the same time, we face constant pressure to keep going.

If we continue in this vein, failure is inevitable.1

Problem #1: It’s all about “health services”!

The Act envisions that universal health care will improve the health of the populace.2

It sets five criteria:

public administration: Healthcare insurance plans must be operated on a non-profit basis by a public authority.

comprehensiveness: The plans must cover all services provided by doctors and in hospitals, if they're medically necessary.

universality: All of the residents of a province must be entitled to the benefits of the plan.

portability: A province must continue to cover its residents when they are travelling elsewhere in Canada.

accessibility: Provinces must provide reasonable access to insured health services on uniform terms and conditions, without financial and other barriers.

As defined by the Act, universal health care primarily involves individual health care providers providing individual health services to individual patients, including:

extended health care services (meaning things like nursing home care).

hospital services (meaning care provided to in-patients or out-patients at a hospital, but only if the services are medically necessary for the purpose of maintaining health, preventing disease or diagnosing or treating an injury, illness or disability).

physician services (meaning any medically required services rendered by medical practitioners).

surgical-dental services (meaning any medically or dentally required surgical-dental procedures performed by a dentist in a hospital, where a hospital is required for the proper performance of the procedures).

Beyond the underlying premise that the best and only way to improve health is through a universal health care system built on individual health care services, there’s an assumption that we can decide which of those services are “medically necessary” and therefore “insured”, eliminating any financial barriers for the individuals accessing them. Knowing that, the federal government then helps the provinces to pay for the insured services.

Problem #2: What’s “medically necessary”?

According to The Canada Health Act: An Overview:

“The Canada Health Act (CHA) sets out criteria and conditions that provincial and territorial health insurance plans have to meet in order to receive the full cash contribution for which they are eligible under the Canada Health Transfer.

The CHA requires that “medically necessary” or “medically required” hospital, physician or surgical-dental services be insured by the provincial or territorial plan. As a result, some health services that many Canadians view as essential to maintaining good health – such as prescription drugs and many mental health services – are not required by the CHA to be insured by the provinces and territories.

Provinces and territories are free to insure other health care services in addition to the ones prescribed by the CHA. This means that the basket of publicly insured health services varies among Canada's provinces and territories.”

Clearly, some important things aren’t insured (life-saving drugs, for example), while some less important things are (like diagnosing male-pattern baldness).

The feds help the provinces to pay for some insured services, but not all, and they’ll withhold money if the province isn’t insuring something the feds see as important.3

Unhelpfully, and unsurprisingly:

“…the Canada Health Act doesn’t define medical necessity or provide a process for doing so. That means individual doctors decide what is medically necessary, usually on a patient-by-patient basis (although they are guided by lists of what provinces cover under their public insurance plans). From time to time, procedures are dropped or added - most provinces, for example, have ‘de-insured’ in vitro fertilization4, and the removal of warts and tattoos.

When a service provided to a patient is medically necessary, it is fully funded by the government and delivered based on the patient’s need, not their ability to pay. If a service is deemed unnecessary, however, patients must pay for it directly.

However, as demands on the healthcare system grow, there is pressure for a precise definition of what’s considered medically necessary; provincial governments would then have a clear idea of what medical services they must provide.

From an Issue/Survey Paper prepared for the Commission on the Future of Health Care in Canada (the “Romanow Commission”) in 2002.

Because the Act replaced two older pieces of legislation, one having to do with doctors’ fees and the other having to do with hospital fees, the health services required to be insured were generally services provided by doctors and hospitals. This made sense in the old medical care paradigm, where the health care system focused on treating sickness, disease and disability and the majority of the costs incurred were doctor- and hospital-related.

In effect, the unstated goal was to protect patients from the financial effects of catastrophic (usually acute) medical illness. Nobody wanted a lack of money to get in the way of a needed cure, and nobody wanted people to end up broke after paying the doctor and/or hospital. To get the doctors on board, the government didn’t question their judgment. Need, not want, was to dictate which services were provided at no charge to the patient.

Medical necessity seemed “obvious”, back then

“Medically necessary is a term that seems straightforward enough on the surface. If you are sick, whatever makes you well again is medically necessary. If you are in good health, what’s medically necessary is what keeps you well.”

From an Issue/Survey Paper prepared for the Commission on the Future of Health Care in Canada (the “Romanow Commission”) in 2002.

At this point, it’s worth reminding ourselves that, according to the preamble of the Act, the pre-existing system that limited government funding to services provided by doctors and hospitals had produced “outstanding” results!

the focus was narrow (you were treating sickness, disease and disability),

the interventions were time limited (you were treated until you got better, or until it was obvious that you weren’t going to),

the diagnosis and treatment options were somewhat limited (there were only so many drugs available), and

it was thought to be fairly clear what worked and what didn’t.5

It’s significant that most of the interventions at that time really were individual services for individual people, and they generally involved acute illnesses. It was, in other words, “traditional medicine”, and it was quite transactional. The physician would assess your subjective complaints, seek out objective findings, make a diagnosis, and offer a treatment plan, all with the goal of restoring or maintaining your health. You got appendicitis, the diagnosis was made, you had your appendix removed. End of story, or so it seemed!

“Medicine is self-limiting because it is aimed at mitigating or eliminating a negative, and that negative is disease. The goals of the process are focused on a narrow range of what would be considered within normal limits. If the disease is eradicated and the patient restored to normal, then the endeavor has ceased and usually will go no further. If the disease is not eradicated, then the physician will continue to treat the patient with the goal of getting as close to normal as possible. Thus, the understanding of a human being that is within normal limits clearly limits the range of the goal of medicine. This inherent limitation has historically prevented medicine from egregious excesses.”

Problem #3: We’ve made things more complicated!

Over time, however, we’ve gained knowledge, the population has aged, and public expectations have increased.

the scope of health care has become much broader (including well-being, prevention, screening, early detection, and chronic disease management).

we’ve started to label some less desirable but otherwise normal features of aging (or life) as “diseases”, through a process known as “medicalization” (examples include erectile dysfunction, osteoporosis, menopause, etc.).

some statistical risk factors have been labelled as diseases (hypertension, hyperlipidemia, and Type II diabetes, for instance). We have moved from treating disease to treating the risk of a disease, which raises questions about which risks matter and what benefit we hope to achieve.6

many medical interventions are lifelong, without clear endpoints.7

the diagnostic and treatment options are more extensive and complex. We have lots of new machines and drugs.

people have been told that health care is free8, comprehensive, and effective.

patients have become less inclined to believe that doctors are the only ones who know which things work and which don’t.

At this point:

“…most medical decisions do not pose clear choices of life versus death, nor juxtapose complete cures against pure quackery. Rather, the daily stuff of medicine is a continuum requiring a constant weighing of uncertainties and values.”

Even people without formal diagnoses have come to see themselves as being unwell. Some patients make their own diagnosis, set their own treatment goals, and/or choose their own preferred service provider; a phenomenon known as “consumer medicine”.

“Through consumer medicine, physicians are no longer healers but variably technologists, body engineers, or entrepreneurs who act to fulfill a patient’s desires…

The patient is now a consumer of healthcare who makes choices and expects those choices to be ‘honored reflexively’. The roles of physician and patient versus vendor and customer frequently alternate back and forth confusing both the physician and the patient. Patients may either mistakenly view physicians as vendors who should dispense a requested medical intervention or they confuse consumer medicine as healthy choices since they are offered by physicians who are traditionally associated with healing in a trusting relationship and environment.

For instance, an OB/GYN physician has been transformed into a reproductive engineer catering not to the goals of health but of a desired fertility state.”

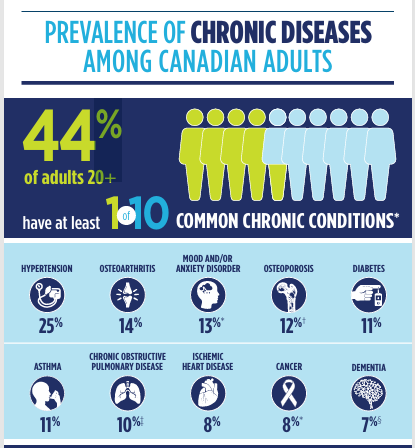

Patients are living longer, and they accumulate problems as they age. At the same time, it’s easier to be labelled as having a chronic disease. In 2015-16, for instance, nearly half of Canadians 20+ laid claim to at least one chronic disease. It’s worse now.

In conclusion, if you see yourself as unwell then you’re not healthy, and if you’re not healthy then you need health care! The health care you need reflects your personal priorities. Because the Act’s version of health care involves individual health services for individual patients, a lot of people “need” a lot of personal medical services!

Problem #4: It’s unaffordable!

We’ve increased life-span, but not health-span. If anything, more people now see themselves as “unhealthy”, starting at a younger age!

It’s puzzling! Is the health of the population actually declining, or is there a problem with how we define health? Does our universal health care system really make people healthier? If it does, why are more people than ever hooked on health care services?

“Medical services are, for the patient, an imperfect means to a desired end (like ‘good health’ or relief from pain), which is not a commodity.”

In pursuit of comprehensiveness, and without ever saying what the term “medically necessary” really means, a broad range of diagnoses and services have crept onto the insured services list. As a result, health care costs have continually risen faster than inflation. It’s become very expensive!

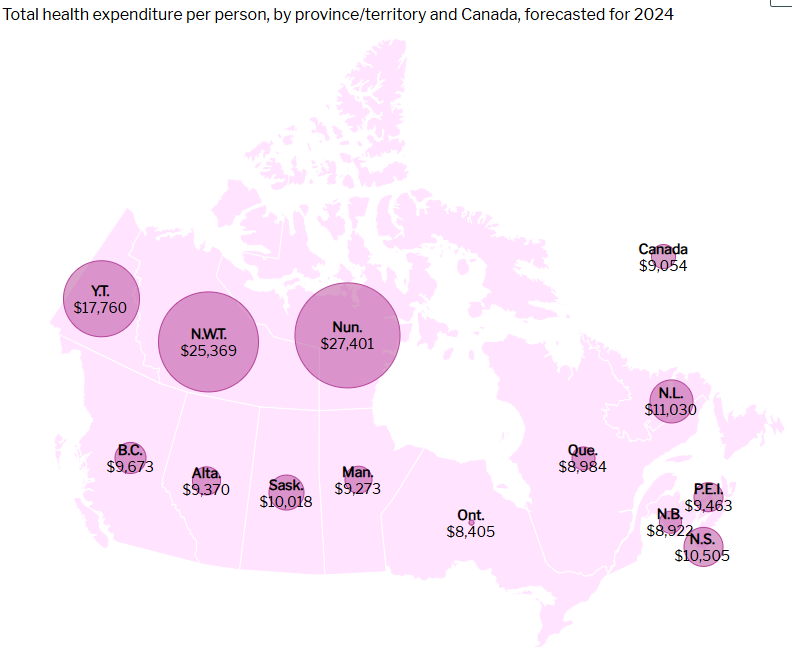

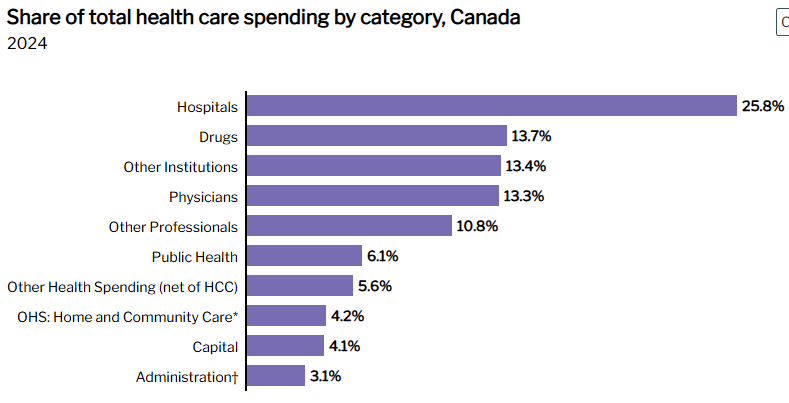

Health-related expenses other than hospitals and physicians now consume over 60% of the pie:

Drugs and nursing home care (aka “other institutions”) have each surpassed physician costs in their share of TOTAL health spending. Home and community care have risen in importance as governments seek ways to keep frail older patients at home, away from expensive hospitals and nursing homes. The non-physician professionals (including dentists, optometrists, chiropractors, massage therapists, pharmacists, home care personnel, psychologists, and counsellors) consume an ever-expanding share of the available funding.

As we aim for a universal and publicly administered system, PUBLIC COVERAGE of services varies from one province to the next, reflecting the balance between what government can afford and the efforts of various groups of patients, providers, and advocacy groups. Those who can establish the treatment of their favorite problem as “necessary” set the public policy agenda; examples include sexual health clinics, bariatric surgery, contraception, abortion, euthanasia, safer supply for addicts, cannabis for chronic pain, etc.

Calling an intervention ‘necessary’ usually means the health plan must cover it and that subscribers* must pay for it…. When necessity is defined as ‘everything that works’, people* can be forced to pay for care that many might deem excessive.”

(* subscribers and * people are taxpayers, in the Canadian context)

You might think, under the circumstances, that the federal government would show some leadership. However, looking at it somewhat cynically:

“The ambiguity of the concept of medical necessity is also advantageous to the federal government. In the face of provincial challenges to the national health insurance standards precipitated by both cost cutting and privatization ideology, the federal government can use the concept of medical necessity to interpret strategically its view of what constitutes a provincial violation of consistent service coverage and reasonable access to medically necessary services across provinces.”

At this point, therefore, we’ve gone well past the point of diminishing returns, pouring more and more money into a system that yields less and less marginal benefit. We aren’t meeting the demand, the quality isn’t great, and yet people want more! Meanwhile, there’s no shortage of alternative service providers hawking their dubious wares and wanting the public to pay for them!

Most importantly, and problematically, we’re now treating problems that affect lots of people, but we’re doing it one person at a time, one visit at a time. In 2022, for example, 30% of Canadians aged 18 and older were obese, up from 21% in 2003. Clearly, it’s a societal problem9 for which you need a public health policy response. Our approach? We offer every third person bariatric surgery, Wegovy, etc., while assuring them that their obesity is a disease.10 That’s not a sustainable approach!

Which brings us back to “medical necessity”!

“Medical necessity provides the conceptual fulcrum of virtually all health plan contracts, seemingly offering a bright promise of excellent-but-not-excessive medicine. Unfortunately, the reality could hardly be further from the promise.”

For lack of a clear definition, whether by accident or by design, we’ve created an extensive, expensive, and ever-expanding system of publicly funded health services, much of which deal with various chronic diseases, the declining function that comes with advancing age, consumer-driven problems, and/or conditions which reflect our living conditions (like stress or obesity).

“…forces have increasingly pressured physicians to serve well-being through the door of health, and this well-being is defined ever more subjectively.

Medicine has now become not just a means of treating an objectively sick person toward health but now a means toward serving any notion of well-being that the patient may embrace.”

And, there’s another problem! In calling something a medically necessary service, we move responsibility from the person with the problem to the person paid to fix the problem. Rather than fixing their problem themselves (or at least taking partial ownership of the solution), patients “contract out” the repair work to a professional. It gets worse when you remove cost from the equation, because the patient is spending someone else’s money, eliminating their incentive to spend wisely.

With everything based on individual services, the entire system becomes quite “transactional”. Patients (and governments) “shop” for services one at a time, in some cases choosing what appears to be the cheaper or more readily available option, without regard for quality.11

These days, many of the services we pay for are reactive, unfocused, time- and labor-intensive, and unsupported by any evidence that they work. Anybody can make an argument that they have a health problem, as long as it involves mental, physical or social distress. Anything can be called a health service if it purports to reduce distress, protect against disease, affect individual lifestyles, emphasize fitness, or promote health. Increasingly, it’s all publicly funded and (badly) administered.12 And, when an election is coming, politicians add to the confusion by promising things they can’t deliver.13

There are solutions (but we have to be willing to change)!

There’s probably little or no chance that things will get fixed before the system collapses completely. The preferred approach is to keep throwing more money into the system, but we will eventually run out of money.

If and when it comes time to fix things, there are things to be considered:

We need to revisit the goals and extent of our public system. Are we protecting against catastrophic expenses, or are we paying for everything? Does public administration mean that the government bureaucracy runs the whole show, or should it simply set standards while insuring part or all of the costs?

We need to revisit the concept of medical necessity, and how it relates to consumer choice. Different patients have different priorities. How do we account for this?

We need to reintroduce patient responsibility. Health care has been framed as a “right”, but what are the responsibilities of those who use the health care system?

We need to stop conflating health with health care and stop assuming that health care means health services. Some things really are public policy issues, and they require bold action.

Above all, we need to stop comparing ourselves to the more dysfunctional and more expensive system next door. Other countries achieve far better results at lower cost.

I’ll explore these and other points in upcoming posts.

“It seems an obvious point that the meaning of necessary services depends, to a large extent, on the goals of the health care system. Yet there is no consensus in Canada on this issue. Goals can be narrowly or broadly defined. Services deemed necessary to achieve one set of health goals - physical health, for example - may not be sufficient to achieve a different one - well-being perhaps being another. It is important for Canadians to develop a consensus on health care goals in order to set the policy framework for discussions of necessary services.”

You could actually make a convincing argument that the system has already failed, but we’ve not yet acknowledged the fact.

There’s even a growing world-wide “universal health care” movement, led by the World Health Organization, aiming for national health systems wherein all individuals can access quality health services without individual or familial financial hardship. Again, the problem is that the pathway to health is seen as building on individual health services.

They did this with access to abortions in PEI, for example.

The document quoted was written in 2002. In-vitro fertilization has since been reinsured in some places, a classic example of politics influencing decisions about our health care system and services.

When I started practice in 1982, for example, a lot of the ancillary services that might make a difference were provided free-of-charge in the hospital out-patient area, including physiotherapy and nutrition counselling. Over time, to save money, those services were either “covertly rationed” (made effectively inaccessible while still notionally being available), or they moved into the community, where they were no longer funded by our provincial government. Some patients were able to cover the costs, either personally or through private insurance, but others could not. These days, you see some people getting useless massages paid for by their health plan while others with significant injuries cannot access needed physiotherapy

Everybody dies in the end. By lowering your risk of one thing, sometimes we change what you die of, but not when you die.

Lowering cholesterol, for example, reduces the risk of a heart attack. However, you’ll treat dozens of people for years on end to prevent a single heart attack. Most people on cholesterol-lowering drugs take the medications and don’t see any personal benefit.

Anything paid for by government isn’t free! We, the taxpayers, pay for it!

If you look at crowd photos now as compared to crowd photos from the 1970’s or 80’s, you’ll realize that the population is noticeably fatter. It could be that millions of people have individually chosen to eat more and exercise less, or it could be that something changed in the food supply and exercise options.

Alarmingly, there are recent published studies claiming that Wegovy is not “just” useful for obesity and diabetes, but it also “helps” osteoarthritis, ischemic heart disease, etc. It stands to reason that weight loss would help with these problems, but do we really want to go down the path of saying that one drug fixes everything?

This is an important point, probably worth exploring in much greater detail in a future post. For the moment, by way of example, consider the increasing transferal of services like “chronic disease management” (CDM) from doctors to pharmacists. CDM is a long-term maintenance program, involving a diagnosis, education, joint goal-setting, regular monitoring, and periodic adjustments to the plan, all in the context of the patient’s overall health and evolving life circumstances. It presupposes an ongoing relationship between the provider and the patient. It’s not a single visit transactional endeavor. Contracting out the work of a family physician (who sees the big picture) to a pharmacist (who sees only part of the picture) makes no sense.

Public administration is another topic for a future post.

One of the parties campaigning in our current provincial election is promising a “centre of excellence for menopause care” and “shingles vaccine for everyone over 65”. Never mind the fact that 15% of the populace can’t find a family doctor, or that emergency departments are often closed. Some things are obviously more “necessary” than others, depending on who votes.

regrettably no politician has the cojones to take up the necessary changes...even the most basic....as focus groups prevent leadership as ever. Most people can see the system doesn't work but they remain passive. Only a full collapse tipping point can trigger change here.