DRUG MYTHS Part 1: When it comes to the rules about "psychoactive drug use", everything is logical and coherent

INTRO, CAFFEINE, ALCOHOL

When you think about it for more than a few minutes, the whole medical, legal, and social policy milieu regarding “psychoactive drug use” makes little or no sense.

Let me explain.

There are many psychoactive drugs

Psychoactive substances are those that affect the function of the central nervous system, altering subjective experience, behaviour, or both.

The list is long, including caffeine, nicotine, alcohol, cannabis, benzodiazepines, opioids, amphetamines, SSRI’s, cocaine, LSD, ecstasy, psilocybin, etc.

The history of psychoactive drug use is probably as old as mankind. And, as long as we’ve been using drugs, we’ve been experimenting with ways to increase their potency and/or find different routes of administration.1

Where are we now? Some drugs are “legal”, others aren’t. Some are “medical”, others aren’t. Some, like caffeine, are so well assimilated into our daily routines and culture that we no longer think of them as drugs. (More on this later, as it’s one of the things that makes little or no sense.)

Different psychoactive drugs have different effects

Prescribed or not, legal or not, psychoactive drugs are consumed specifically for their effects on various functions of the brain. If they didn’t affect the brain, we wouldn’t take them — it’s as simple as that! The effects for each drug depend on which specific parts of the brain are affected. Some drugs increase brain activity (i.e. stimulants and hallucinogens) while others decrease it (i.e. sedatives).

There’s no way to ensure that the drug taken will find its way only to one specific area of the brain. That being the case, all psychoactive drugs come with both useful effects (which we’ll call “benefits”) and unwanted side effects (which we’ll call “harms”). The distinction can be contextual — hallucinations may be desirable when drugs are taken for “fun”, but not when they are given to a hospitalized patient for pain. There is no situation in which the use of drugs comes without some sort of risk — this is why pragmatists talk about “harm reduction” rather than “harm prevention”.

While no listing is going to be all inclusive, a 2011 international survey of drug users suggested the following “benefits”:

Sociability (Lose inhibitions, be more sociable, feel more confident, feel closer to people, have more empathy, feel part of a social group)

Enjoyment (Enhance activities, enhance sense of fun or humour, help with creativity and abstract thinking, increase sexual function and enjoyment, feel elated and/or euphoric)

State of mind (Open up to new experiences, alter senses, increase existential awareness, find meaning in the self and the world, alter consciousness, help to get out of your head, escapism)

Relieve physical pain and symptoms

Relieve anxiety and depression

Feel more relaxed, relieve stress

Change appearance of body (bulk up or lose weight)

Help wake up, have more energy

Help to get to sleep

Improve attention, memory and concentration

Of note, the benefits vary from drug to drug, user to user. With a few exceptions, they are immediate, personal, and idiosyncratic. One man’s pleasure can be another man’s poison — your experience may differ from mine, in terms of both the actual effect of the drug and your interpretation of that effect as pleasurable or not. Some take drugs to wake up, others to get to sleep, some to escape, others to be more engaged.

That same survey also listed the following harms:

Short-term physical risks (like overdosing and accidents)

Long-term physical risks (like cirrhosis of the liver)

Risks associated with injecting (including hepatitis, HIV, etc.)

Physical dependence (including the development of tolerance and withdrawal effects)

Psychological dependence (cravings)

Risks to society (damaged relationships, crime, car accidents, etc.)

Bingeing (using more than planned, for longer than intended)

The harms also vary from drug to drug, user to user. They can be immediate or long term, trivial or fatal. Many are personal, but several affect others. A number of them are reflected in the diagnostic criteria for substance use disorders, but you don’t necessarily have to reach the state of problematic use to see the harms — drunk drivers can kill people even when they aren’t alcoholics.

Balancing benefits and harms

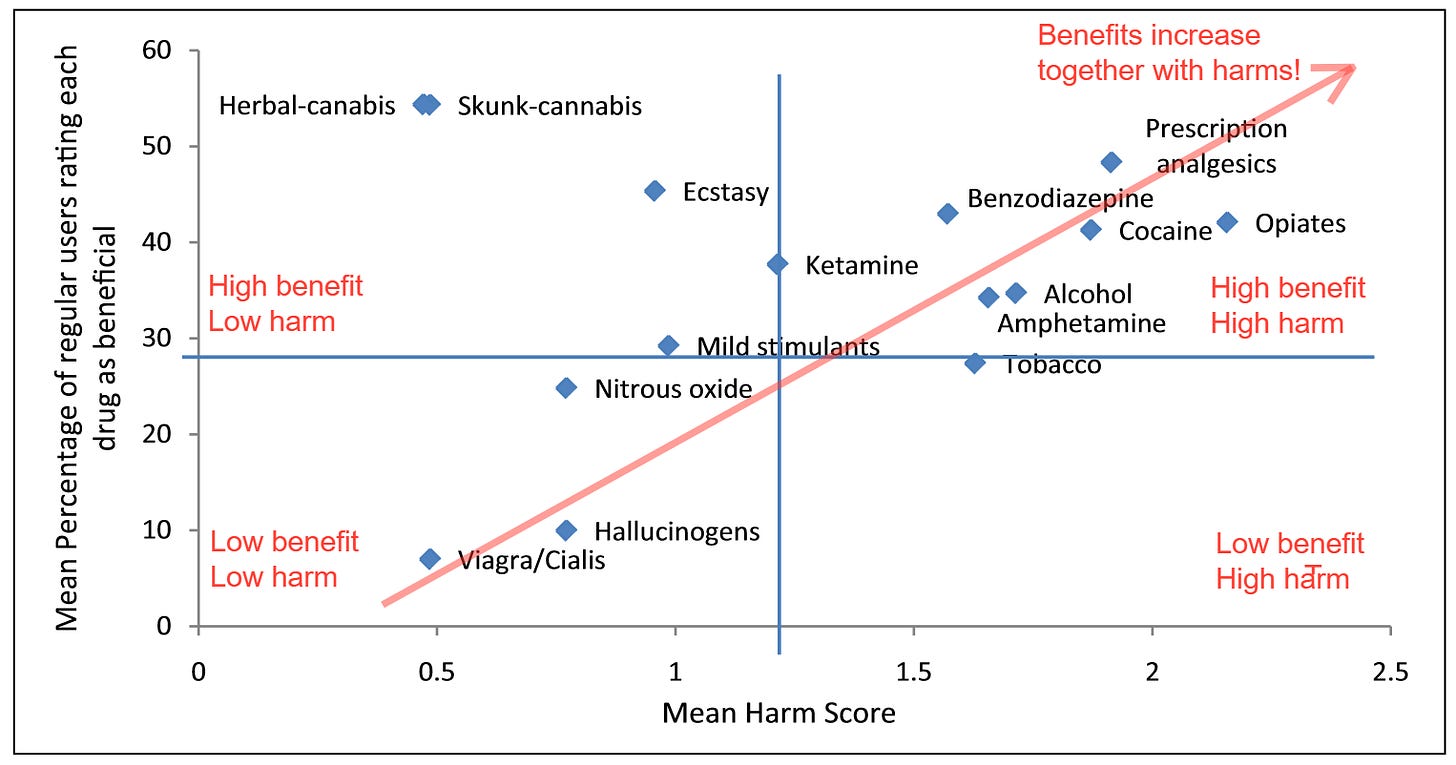

Drug users (and doctors) can all agree that some drugs are more harmful than others, individually and collectively, and some harms are more consequential than others. The drug users who were surveyed saw it this way:

Things like cannabis and ecstasy seem to be “high benefit, low harm”.

The hallucinogens are “low benefit, low harm”2. Caffeine wasn’t surveyed (probably because drug users, like everyone else, no longer consider it a drug), but I’m guessing it would be in that quadrant as well.

Pretty well everything else is “high benefit, high harm”.

Given the emerging evidence about cannabis3, now that it’s been legalized in a number of places, with a corresponding increase in usage, I’m wondering if its harms weren’t underestimated. If so, it would move a bit to the right on the graph, and the surveyed drugs would then all fall more or less on a line where the risk and benefits increase together, as shown by the arrow. In other words, unsurprisingly, the more a drug affects your brain, the more likely it is to have both benefits and harms. The perfect drug (all benefit, zero harm) has yet to be invented!

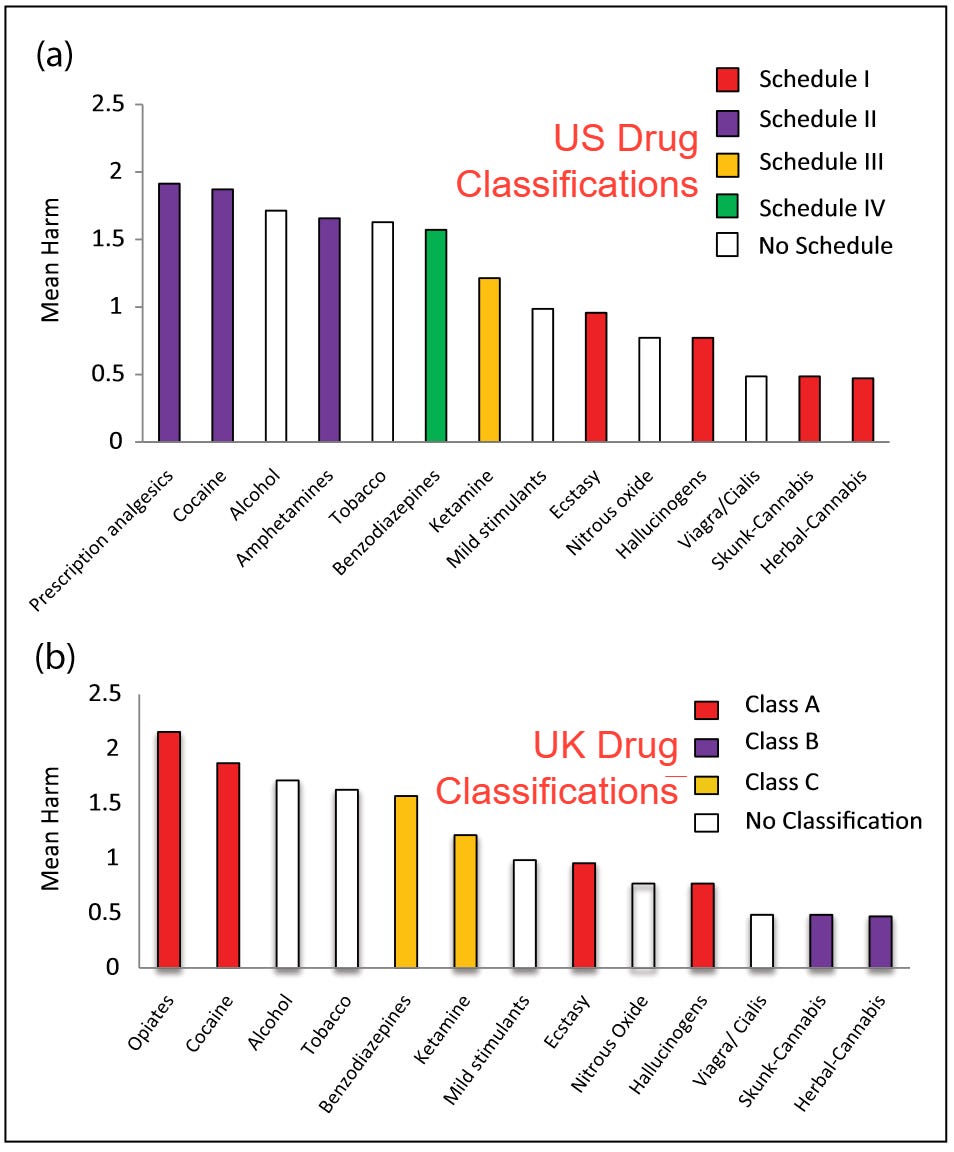

Interestingly, and this is one of the things that makes no sense, there is no correlation between the users’ harm ratings and the legal classifications of the various drugs. The fact that those legal classifications vary from one country to the next is another thing that makes no sense.

Psychoactive drugs are used for different reasons

Depending on the context, different drug effects assume greater or lesser importance.

Hallucinogens seem to have religious uses and are, as such, often consumed under the guidance of spiritual and religious leaders. I’m assuming this is a “niche” market.

Analgesics and sedatives have medical uses and are prescribed by doctors. While you would think that everyone has access to the same “science”, the prescribing patterns and the specific drugs used vary enormously from one country to the next and over time. This variation is another thing that makes no sense! The increasing use of opioids in chronic pain, for example, is seen as a contributing factor in the opioid crisis, perhaps because the benefits were exaggerated and the risks downplayed or ignored. I’ve written about that in previous posts.

Where things get even more interesting (and illogical, in terms of the societal response) is when individuals choose to use psychoactive drugs either because those drugs are seen as “normal” or for their own personal reasons, including “self-medication” and “pleasure”.

Socially accepted “normal” drug use: caffeine

Some drugs have become part of our culture, to the extent that we no longer see their use as anything out of the ordinary.

Caffeine, for example, is ubiquitous, occurring naturally in many plants (most notably tea, coffee, and cocoa) and more recently as a synthetic additive in many foods and beverages (including “energy drinks”). Known to promote arousal, alertness, energy, and elevated mood, with some weak analgesic properties, it is used by 80% or more of the inhabitants of affluent countries, making it the most widely consumed psychoactive drug in the world. However, caffeine users don’t think of themselves as taking caffeine — they focus on the beverage, not the active ingredient.

Caffeine use, as a result, seems “normal”, an integral part of the daily routine. Who doesn’t start their day with a cup of coffee (or tea) and socialize with others over a caffeinated beverage during breaks? Entire business empires have been built on the sale of caffeine-containing products! A Tim Horton’s franchise is a license to print money.

Interestingly, caffeine can be manufactured and packaged in tablet form. Conversely, coffee, tea, and cocoa can be decaffeinated, and the caffeine, in and of itself, probably isn’t contributing much to the flavour (although purists will probably disagree). As such, it’s theoretically possible to divorce the psychoactive effects of caffeine use (which peak 15 minutes to 2 hours post-ingestion) from the immediate sensory experience of drinking the beverage. Even so, the vast majority of the caffeine consumed in the world is taken in the form of food and beverages, rather than pills. Perhaps, at least in part, the sensory and social experience matters as much or more than the psychoactive effects? Popping into Tim Horton’s or Starbucks for a caffeine pill just wouldn’t be the same, would it?

Regardless of the form in which it’s ingested, caffeine is physically and psychologically addictive, which may explain why there’s a coffee shop on every street corner! We start drinking it for the taste and keep craving it because we’re hooked. Those who quit using caffeine will, within 18-24 hours, develop headache, drowsiness, impaired concentration, work difficulty, depression, anxiety, irritability, nausea or vomiting, and muscle aches and stiffness, all lasting up to a week. Resuming regular caffeine intake will take all that misery away.

So, you think you need that morning cup of coffee to perk you up, or because you like the flavour and experience, but in part you need it to stave off your caffeine withdrawal symptoms! Being physically and psychologically dependent on caffeine, technically speaking you’re actually an addict! You’re not alone, however. A 1998 survey of caffeine users, based on the generally accepted criteria for substance use disorders, found that:

56% described a strong desire and/or unsuccessful attempts to stop using caffeine

50% spent a great deal of time supporting their caffeine habit (driving miles and sitting in lineups at the Tim Horton’s drive-through, for example)

28% used more caffeine than intended

18% had recognizable withdrawal symptoms

14% continued using caffeine despite knowledge of its harmful effects

8% had developed tolerance, and

1% had even foregone other activities to facilitate their caffeine use.

Even so, because caffeine is generally not thought to be associated with any “significant” health hazards when taken in “typical” doses, you won’t hear the experts recommending “responsible use” of caffeine or advocating for “safer supply” (i.e. decaffeinated beverages).4 Coffee drinkers are not sent outdoors to indulge their habits in isolation! Tea drinking in parks or public spaces isn’t banned! While pregnant women, children, and individuals with mental illness are considered vulnerable to caffeine’s harmful effects, you won’t see warning labels on coffee cups. There are no age restrictions, and the makers of energy drinks can market their products to youth. The Red Bull isn’t hidden behind the counter at the pharmacy. Even though, in high enough doses, caffeine can induce fatal cardiac arrhythmias, you won’t hear any argument for safe ingestion sites including defibrillators!

Our societal response is restrained. Acting as if they’re aware of the risks and doing something about them, our governments “regulate” caffeine, but not really. We have regulations limiting the caffeine content of various foods and beverages, added caffeine must be listed as an ingredient on food packaging, and there are, believe it or not, recommended daily limits for caffeine intake. For the most part, however, these are widely ignored.

Caffeine use, for better or for worse, is simply a fact of life.

Socially accepted “recreational” drug use: alcohol

As with caffeine, alcohol use, at least in non-Islamic societies, has come to be seen as “normal”, an integral part of life. Entire business empires depend on the sale of alcohol-containing products. Now, some even sell caffeine-laced alcohol!

As with caffeine, alcohol is the active ingredient in various beverages. Sure, you can get “pure” (95%) alcohol, such as “surgical ethanol”, but it’s not readily available. The closest thing on the open market would be vodka, which is essentially 40% alcohol in water, with no impurities (which makes you wonder how companies can market their particular vodka as being “better” — alcohol is alcohol and water is water, after all!). Alcohol by itself is relatively flavourless, so the pleasurable experience of alcohol consumption comes from (a) the immediate taste of the additives and various impurities (why we prefer one brand of beer, one variety of wine, or one specific type of hard liquor), and (b) the slightly delayed psychoactive effects of the alcohol you absorb.

Our governments are heavily dependent on revenues related to the sale and taxation of alcohol. In 2023-24, for example, the Nova Scotia Liquor Commission sold $753.4 million worth of alcohol, amounting to about $1,000 per person per year5 for those of legal drinking age, about 1/3 of that being profit. In 2016-17, Canada collected $1.6 billion from excise taxes on alcohol, and $634 million from goods and services tax (GST) applied to alcohol.

The belief is that alcohol use brings mental, emotional, social and/or physical benefits, as you might see with other forms of recreation, and so we consume it with meals, entertainment, and sports, seeking additive benefits. Alcohol advertising, overt and covert, reinforces the pleasurable linkage with artistic, cultural, and sporting events. A good meal plus a good glass of wine is more enjoyable than either alone. Spectator sports are more enjoyable when taken with beer. The picnic in the park will be better with alcohol, now that the laws are being relaxed. For those so inclined, there are even drinking games, wherein alcohol becomes the entertainment!

“Alcohol use is a useful example of how much the use of a substance has been so deeply ingrained in social and cultural practices that it is implicitly and by default seen as “recreational”. Hardly anyone would speak about “recreational” alcohol use: it is taken for granted that it is. And if it is not, the users are stigmatized.”

Framing substance use as “recreational” is neither accurate nor helpful for prevention purposes, Sanchez et al., 2023

Through it all, we assume, for the most part, that most alcohol is used “responsibly”, for “pleasure”. The alcohol industry would have us believe that alcohol in and of itself is unproblematic, maybe even healthy, as long as drinkers drink “moderately” and behave. Marketing campaigns, while reminding us that alcohol and pleasure go hand in hand, remind us to “drink responsibly” and “don’t drink and drive”. The implication is that the harms are entirely avoidable.

There’s a naive assumption that this recreational use of alcohol involves individuals making decisions based on their rational consideration of the benefits and the harms. However, when choosing to have a glass of wine with supper, where the benefit is immediate and the risks minimal, people aren’t drinking with an eye on their health, they’re drinking for pleasure! Things become less clear, perhaps, when they head out with friends for an evening of partying, or when they spend every evening in front of the TV, drinking alone.

Drinking, in other words, doesn’t necessarily involve a rational decision. For one thing, once consumed, alcohol affects the ability to make decisions (decision quality decreases as the amount consumed increases), and it’s worse in the face of peer pressure! Furthermore, it’s fairly well known that people making decisions tend to value immediate personal gains over long term pains and the possibility of harm to others. Besides, the majority of casual drinkers do not experience individual or immediate harm. As such, they can be intellectually aware of the potential harms and still see the risk of harm as being negligible or irrelevant to them. They don’t take a drink with the intention to later wreck the car. After all, they’ve never crashed the car before! They might start off with the intention to have a single drink but then find themselves having a good time, unable to refuse the second and subsequent drinks. For the addicts, it’s no longer a choice; they’ve “lost control”.

“Additionally, from an evidence-based prevention perspective, focusing on a public discourse on the warning about harms and health risks is useless. Although accurate and balanced information on these aspects is an essential educational right, it is an — albeit very popular — illusion to believe that better knowledge about harms would — by itself — have a mitigating effect on substance use behavior, even less in young people and even lesser if the potential harms are long-term.”

Framing substance use as “recreational” is neither accurate nor helpful for prevention purposes, Sanchez et al., 2023

For all those reasons, and more, public education about responsible drinking doesn’t really work. You can’t avoid all the possible challenges and harms related to substance use by improving and fostering individual choices and responsibility. Controlled and carefully considered “recreational” use might be the reality for some people, but it’s a delusion for many.

Despite the evidence, the latest Canadian Low Risk Drinking guidelines suggest that “Drinking Less Is Better”, offering guidance which they say is based on the principle of autonomy in harm reduction and the fundamental idea that people have the right to know that all alcohol use comes with risk. In short, they want you to be informed and make your own decisions!

Societal standards might play a role, but they can be misleading. While drinking seems to be something that “everyone is doing”, less than 80% of Canadians report alcohol use in the past year, and that drops to about 60% for the past 30 days. In this context, it’s worth remembering that there are entire countries where alcohol use is completely prohibited. The extent to which your social circle drinks, therefore, depends in part on how much you drink and how it fits in with your social life. You won’t see your non-drinking friends not drinking, for example, because they’ll be doing other things (possibly with other people) when you are drinking. When drinking, you’ll likely be with other drinkers. It’s a self-fulfilling prophecy — it will inevitably appear to you that you are doing what everyone else does.

While we have laws specifying where, when, and to whom alcohol can be sold, and where, when and by whom it can be consumed, the official rules are getting more relaxed over time. Again, the theory goes that drinkers can make wise choices, and that they’ll listen to the advice that “less is better”. However, underage drinkers have no trouble obtaining a supply and drinking ages have been lowered, making it even easier. Government-operated stores with strict sales policies are being supplanted by privately-run stores with looser standards. Drunks face few obstacles to getting drunk. Bars and restaurants that break the rules are punished, but it’s rare. Drunken brawls are common. Drunk drivers still kill people, despite laws saying they shouldn’t be driving. Problematic drinking is a big problem!

Alcohol consumption in Canada was associated with approximately 15,000 preventable deaths, 90,000 preventable hospital admissions and 245,000 potential years of life lost in 2014. The collective impact of alcohol use on health care, crime and lost productivity was estimated at $14.6 billion, higher than the costs of tobacco use and the costs of all other psychoactive substances combined, including opioids and cannabis.

(source)

Of course, there’s a spectrum of alcohol use, ranging from abstinence through very occasional drinking to regular drinking to constant harmful drinking, unable to stop (otherwise known as alcoholism, or alcohol use disorder). Harm can occur anywhere along the spectrum, whether alcohol is used responsibly or irresponsibly, regularly or not, recreationally or habitually, a lot or a little. The occasional drinker can over-indulge and have an accident. The regular drinker might be drinking once a week and getting fall down drunk every time. The daily drinker can end up with liver disease.6 The alcoholic can lose their job and family.

While there is stigma associated with public drunkenness, drunk driving, and alcoholism (the harms that affect others), addiction advocates argue that the stigma itself represents an additional form of harm (affecting the addict), a barrier to their getting help when needed. They would prefer you to avoid expressing your disgust, using more neutral terminology such as “persons living with alcohol use disorders”. Conversely, some argue that the unfavorable opinions of others (and legal consequences) can be a motivating force.

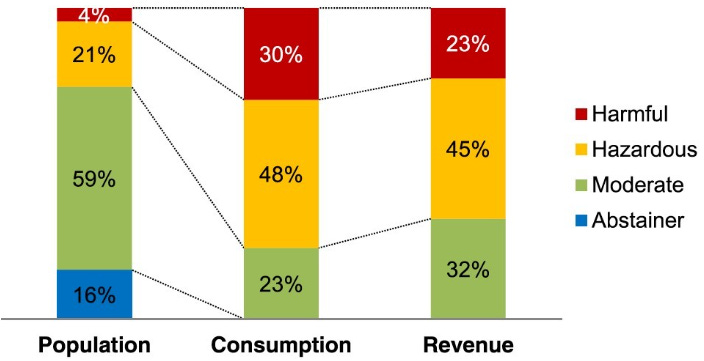

Where things get interesting is when you break down the patterns of alcohol use in relation to the total consumption. Research done in the UK (and there’s no reason to believe that Canada would be different) shows the following:

The top 4% of drinkers (the “harmful” drinkers) account for 30% of the total consumption of alcohol, and 23% of the revenue. (Unsurprisingly, I guess they favour the cheap stuff!)

The next 21% of drinkers, the “hazardous” ones, account for 48% of the total consumption, and 45% of the revenue.

Together, the top 25% of drinkers consume almost 80% of the alcohol and incur 2/3 of the costs!

Most users are not abusers (they don’t use it at all, or maybe they use it mostly for pleasure?), but most of the alcohol used is used “irresponsibly”, (assuming that’s a fair conclusion to make about somebody else’s usage pattern).

Pause! Think about that for a minute! Despite their caring messages about drinking “responsibly”, our governments are making a heck of a lot of money selling alcohol to people with significant alcohol problems, as are the companies that manufacture and distribute liquor. 78% of the alcohol supply isn’t really being used primarily for pleasure, is it? If it is, then a small group of people are having way too much fun! While it seems good that the government takes more money from those most at risk, is it really ethical for government-owned liquor stores to keep selling addictive substances to addicts? Taken as a whole (i.e. including societal and health care costs), do the revenues really exceed the expenses?

So, as with caffeine, alcohol use, for better or for worse, is a fact of life for a good-sized chunk of the population. Recreational alcohol use is heavily promoted. Unlike caffeine, however, alcohol can be harmful. While some use alcohol responsibly, purely for pleasure, it becomes a personal problem for a lot of people. Their problems affect everyone, through the consequences of their behaviours, the effect on their health, and the associated costs. Acting as if they’re aware of the risks and doing something about them, our governments regulate and operate the alcohol business, while encouraging alcohol users to make wise decisions before imbibing. Paradoxically, at the same time they are relaxing the rules.

There are ways to reduce our overall consumption of alcohol. I won’t go into them in detail, but you can read about them here. Suffice it to say that many of the things our government is doing fall into the “ineffective” and “potentially harmful” categories.

In the next post: nicotine and cannabis

In this post, I’ve introduced the concepts of psychoactive drug use and discussed the situation with caffeine and alcohol, both of which are seen as a “normal” fact of life. Caffeine seems harmless. Alcohol is well known to be harmful.

In the next post, I’ll talk about nicotine, the use of which is legal but increasingly stigmatized, in part because smoking is harmful. There are, however, other ways to use nicotine.

I’ll also talk about cannabis, which was illegal but is now legal. The theory goes that it’s pretty innocuous, but is that really true?

See, for example, Marc-Antoine Crocq’s article entitled Historical and cultural aspects of man’s relationship with addictive drugs.

Viagra and Cialis were included in the survey, apparently not because they are psychoactive, but rather because they are taken recreationally. It’s interesting that they came up as “low benefit”. I’m assuming that’s because the psychological benefit might be an indirect effect of enhanced sexual performance, rather than a direct effect on the brain.

See, for example, “Balancing risks and benefits of cannabis use: umbrella review of meta-analyses of randomised controlled trials and observational studies”, a 2023 article which concludes that “Convincing or converging evidence supports that cannabis use is associated with poor mental health and cognition, increased the risk of car crashes, and can have detrimental effects on offspring if used during pregnancy. Cannabis use should be avoided in adolescents and young adults (when neurodevelopment is still occurring), when most mental health disorders have onset and cognition is paramount for optimising academic performance and learning, as well as in pregnant women and drivers.”

As the epidemiologist Geoffrey Rose pointed out, however, when everybody in a society is exposed to an agent, it becomes difficult, if not impossible, to tell whether that agent is actually causing problems. Since virtually everyone is exposed to caffeine, where would we find a control group of people who don’t consume caffeine to see whether their health risks were actually lower?

Or, more specifically, $1,500 per male per year and $500 per female per year, as men typically drink three times as much as women. When you consider that only 80% of the population reports using alcohol in the past year, the numbers rise to $1,875 for males and $625 for women.

The experts have recently concluded that “there’s no safe amount” to drink, claiming that alcohol, among other things, is a carcinogen. By analogy to cigarettes, they say that the risk of cancer increases with every dose of alcohol.

Excellent post. As you probably know, I treated substance abuse for years. It is a minefield of hypocrisy and discrimination that addicts face which has become institutionalized. What practitioners do to treat it is often flawed in its methodology and outcomes. That’s why a colleague and I wrote this book:

https://open.substack.com/pub/alexaudette/p/the-intelligent-self-abuse-manual?r=1z6cwm&utm_medium=ios

Which is a humorous deeper dive into substance use that we wrote for our patients from a harm reduction perspective. We covered every substance of abuse just as you are doing. Although you are probably the strict uncle, whereas we are the permissive one.