Medical Myth #2: If public Administration is best, then more of it must be better

A brief history of the fine mess we call Medicare

A recent editorial by Andre Picard in the Globe and Mail made reference to a series of articles written by Tara Kiran for the Canadian Healthcare Network. Picard and Kiran described health care in Denmark and the Netherlands, wondering why we aren’t like them.

In terms of how care is delivered, I found the articles informative. However, even though health care systems are there for the sole purpose of providing health care services, there’s more to it than that.

It has been said1 that “every system is perfectly designed to get the results it gets”. That being the case, I felt both authors missed the mark by failing to fully consider how the health care systems in Canada, Denmark, and the Netherlands are designed. The short version of the story is that Canada invested heavily in the concept of “public administration”, doubling down on this approach even when it’s visibly failing.2 Other countries chose other paths.

In this post, I’ll review the evolution of health system governance (aka “public administration”) in Canada. In a subsequent post (or posts), I’ll compare and contrast the governance structures across the three countries, linking it back to its impact on care delivery.

“Public administration” is one of five foundational pillars in the Canada Health Act (which I’ll refer to henceforth as “the Act”). By law, the health care insurance plan covering core “Medicare” services (hospital services3, physician services and surgical-dental services) in each province must be “administered and operated on a non-profit basis” by “a public authority”, based on national standards set by the federal government.4

When applied unquestioningly and inflexibly, there are more than a few problems with this approach. There are even more problems when the same approach is extended to services not governed by the Act. It gets even messier still when you remember that it’s just the administration and operation of the insurance plan that is supposed to be “public”, with the Act saying nothing about actual health care services, which can be, and often are, “private”.

Back to the basics

Taking it back to first principles, consider the following:

“Essentially, there are three responsibilities in healthcare:

first, the financing of health services through taxation, social insurance contributions or private means;

second, the provision of healthcare which can be carried out in state-run facilities respectively by state-based actors, in societal-based facilities, or in private for-profit facilities respectively by private actors; and

third, the regulation by these actors of the various aspects of financing and provision.

…. in ‘real’ healthcare systems, the elements ‘state’, ‘societal’ and ‘private’ tend to coexist along all three dimensions, and especially when analysing changes over time the mix within categories must be taken into consideration.”

Healthcare System Types: A Conceptual Framework for Comparison, Wendt et al.

In other words, health system financing can come from the state (taxation), social groupings (insurance), or the individual (out-of-pocket). In most systems, ours included, there’s a mix of the three, with one predominant.

Likewise, health care services can be provided by the state (public hospitals), social groupings (religious hospitals), or private individuals or organizations (physician-owned medical clinics). Any of those can be “for profit” or “non-profit”, although those operated by the state are more likely to do so on a “non-profit” basis.

Regulation is a complicated topic, but it can be done by the state, social groupings, or individuals.

There is the regulation of the actors themselves, as when the state has legislation specifying which facilities can call themselves hospitals, which agencies can provide health insurance, or which providers can call themselves doctors. This form of regulation can also be “societal” (as when hospitals and doctors participate in various forms of peer review5, or when social insurance providers set their group standards), or “private” (as when doctors complete Self-Reflection and Physician Practice Improvement work).

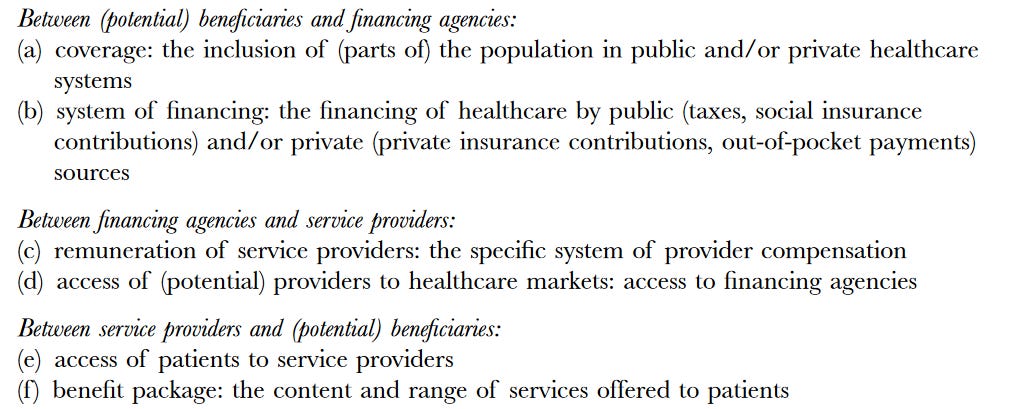

There is also regulation of the interactions between the patients, their providers, and the insurers:

In a fully private system, hospitals and doctors negotiate their fees directly with patients. In a fully state-run system, the state might simply decree what those fees are.

So, with three dimensions (financing, care, and regulation), each with three possible management styles (state, societal, and private), you’ve actually got 27 different ways to set up a health care system, more if you consider the various “mixed” models. The good news is that not all of them exist, in the real world.

Our system differs from Denmark and the Netherlands, and it’s not the same as it was when the Act was first passed.

Which brings us back to the beginning.

The Act is only about financing!

The Act relates to the federal financing of provincial (and territorial)6 health care insurance systems, protecting patients from financial losses relating to care provided by hospitals, physicians and dental surgeons7.

It’s neither “universal” nor “comprehensive”. It doesn’t include, for example, prescription drugs, community-based rehabilitation services (physiotherapy, etc.), long-term care, some types of mental health care (i.e. psychologists), community dental care, and vision care. Some of these gaps have grown, as fewer and fewer services are delivered exclusively in hospitals.

“Universal” (or “public”) health insurance in Canada, is, therefore, “narrow but deep”, providing full financial coverage for a VERY limited range of services.

Who pays?

The full costs of the insurance for those core Medicare services are paid from state tax revenues.8 Extra-billing and user charges (including public insurance premiums) are not permitted, because they would “impede reasonable access”.

For some segments of the population, depending on the fiscal capacity and policy priorities of the individual provinces, public insurance coverage has been expanded to include some of those other non-core health services. However, without national principles or federal funding, public coverage for these services varies considerably.

At present, roughly 70% of total health expenditures are financed publicly. Just over half of that amount goes to hospital and physician services, with the rest divided between public health, long-term care, prescription drugs, infrastructure, administration, and research.

The remaining 30% of total health expenditures reflects private health insurance and out-of-pocket payments, for things like prescription drugs, dental care, vision care, other health professionals, long-term care, over-the-counter drugs, and personal health supplies.

Thus, it’s a fact that the financing of health care in Canada is mixed, with a large chunk being private.

What did they mean by “administer and operate”?

The requirement for public administration and operation was (and still is) limited to managing the financing of Medicare as an insurance scheme.

The delivery of care by a provider (doctor or hospital) to a patient is a separate question.

Prior to the inception of Medicare, many hospitals were public or private9, mainly non-profit, institutions, each with their own administrative structure. A very limited amount of government supervision existed, mainly through policies financing the care of indigent patients.

After the introduction of Medicare, the provinces provided the vast majority of hospital funding. Still, the day-to-day delivery of care remained the responsibility of the hospital boards, subject to high level government regulation.

Doctors were (and still are) independent, private professionals caring for individual patients. The initial focus of Medicare was to ensure that they were reasonably and consistently compensated for their services, at standardized insurance rates determined through negotiations and, if necessary, a dispute resolution process.

So, in the beginning, the “administration and operation” involved only the financing of the government health insurance plan:

ensuring that patients received hospital and doctor services at no cost, and

ensuring that the hospitals and doctors were fairly paid for the work they did.

Hospitals and doctors delivered care privately, financed through public insurance. Hospitals were regulated by government; doctors were self-regulating professionals.10

It was taken for granted that hospitals and doctors were only doing things that were “medically necessary”. That which was done was going to be paid for.

What part is meant to be “non-profit”?

The original requirement that Medicare be “administered and operated on a non-profit basis” pertains only to the financing and operation of the insurance scheme, rather than the delivery of care or the regulation of the entire health care system.

For context, not-for-profit (NFP) organizations are those which provide services to the community without the goal of making a profit, where no part of their income is paid or made available for the personal benefit of any proprietor, member, or shareholder. Generally, they are self-governing, with boards of directors accountable for using resources wisely.

The delivery of care is another matter.

It’s often true that a hospital delivering care has no profit-seeking shareholders. However, in the case of a privately-owned surgical centre that provides Medicare-insured services under contract, it’s easy to imagine that somebody owns the business and takes home a portion of the proceeds as a return on their investment. So, some hospital-type care is “for profit”, and some isn’t, and that’s perfectly OK, under the Act.

It’s also pretty obvious that Medicare dollars paid to doctors ultimately accrue to their personal benefit. Are they simply receiving fair remuneration for their work, or are they turning a profit? Either way, it’s OK.

Things get even murkier when you consider the non-core, publicly funded health care services, such as ambulance operators, private home care agencies, pharmacies, and nursing homes, many of which clearly make a profit. By the Act, it’s OK if they do.

There’s been administrative creep…

Over time, the provinces have taken a much broader view of their administrative powers, as they relate to the core Medicare services.

…in hospitals…

The vast majority of hospitals are now government owned and operated, with global budgets set directly (by ministries of health) or indirectly (through budget allocations to health authorities).

Only a small number of hospitals and hospital-like facilities remain private, delivering specific services under contract.

Either way, there’s no longer any meaningful separation between the purchaser and provider of hospital services, because hospitals get over 90% of their funding from the state. In consequence, hospital administration has been folded into regional or provincial health authorities, eliminating local health care organizations and their boards of directors.

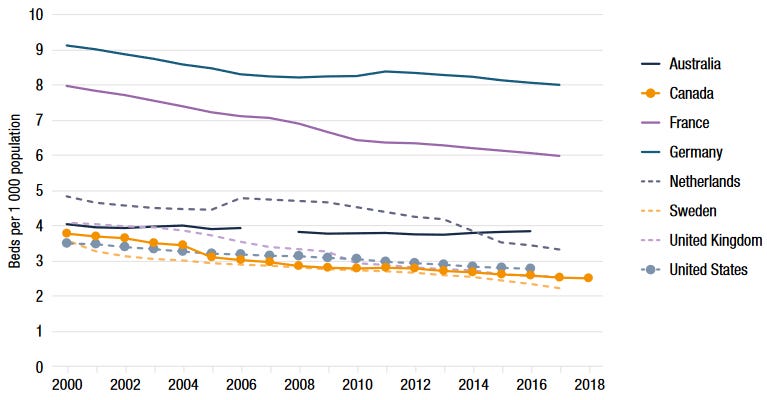

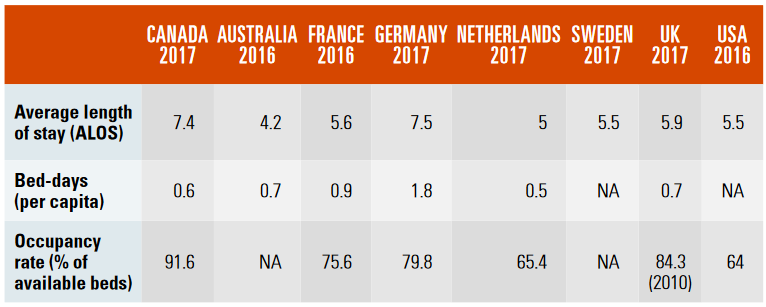

While this centralization may have been justified on the claim that it would “reduce bureaucracy”, there’s no doubt that it has also had the effect of limiting hospital resources (and therefore costs). As shown below, Canada has relatively fewer hospital beds than many other countries, even though our hospitalization rates and average length of stay are higher, resulting in much higher occupancy rates (and, inevitably, hospital overcrowding). The system gets the results it’s designed to get!

…and for doctors

In theory, most primary care and specialist physicians are still independent, for-profit professional contractors, delivering care privately.11 However, with 98% of physician revenue derived from public insurance, the original fee-for-service payment model has gradually evolved and, in many cases, been replaced. Each new funding arrangement brings more government control and less physician autonomy.

The emphasis has shifted away from ensuring that doctors are fairly paid for medically necessary work (as determined by the patient and their doctor) toward the state stipulating where doctors work, who they look after, and what they do or don’t do for (or to) their patients.12

The guiding principle of medical necessity has shifted toward “what the government can afford” and/or “what the government thinks doctors should be doing”, often with little or no public (or medical) input.13

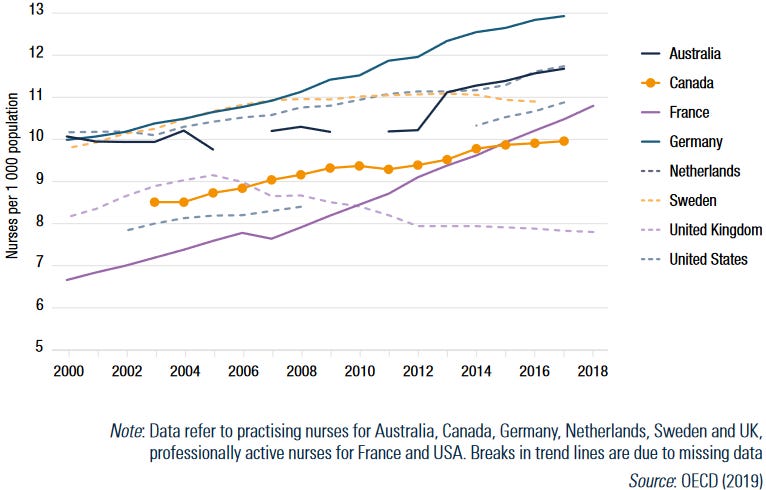

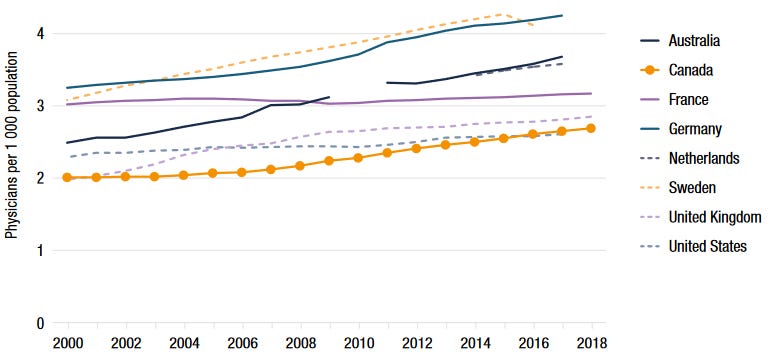

For doctors, as with hospitals, the separation between the state insurer and the private providers is vanishing. Going beyond the financial relationship, the government has used its regulatory levers to limit the supply and distribution of physicians, leaving us with fewer physicians per capita than many other countries.14

The boundaries between public and private are disappearing

Clearly, provincial governments have moved beyond financing the core, publicly insured health care services, taking an ever-increasing role in regulation, administration and delivery.

At the same time, public financing, regulation, administration and delivery has crept into selected non-core health services, including, for example:

prescription drugs for the elderly and financially challenged

long-term care

some types of mental health care (i.e. psychologists)

community dental care, and

some types of vision care.

Historically, many of these services were delivered privately by individual providers and/or organizations, including clinics, nursing homes, pharmacies, etc., all funded by private health insurance and out-of-pocket payments. Not all were regulated by governments. Some were “for profit”, others weren’t.

However, as with the hospitals and doctors, once the state starts to pay for some part of these services, they’ll ultimately seek to regulate, administer and then operate the sector, even though the Act doesn’t apply.

With nursing homes, for example, the facilities are public and private, for-profit and non-profit. Because all nursing homes are regulated and licensed, new ones don’t get built without government approval. Sure, patients pay for their own care, or at least part of it, until their funds run out, but there’s no longer any patient choice. The government decides which patients are eligible for nursing home care, which services they’ll receive, and which home they’ll be placed in.15

Similarly, our federal government recently introduced a national dental care program, to be implemented in conjunction with the provinces. In doing so, they’ve specified which citizens are eligible, which services are covered, how much the government will pay, and how the dentists will get paid.16 While patient enrollment and dentist participation are both “voluntary” (for now), the intrusion of government into what was formerly the private domain alters the landscape.17

Public administration and operation subsume delivery and regulation

So, we started with the Act requiring that the financing of hospital services and physician services in each province be “administered and operated on a non-profit basis” by “a public authority”.

We’ve ended up with provincial and federal governments vastly expanding their mandate:

They are no longer limiting themselves to the core services. They’ve expanded into non-core services.

They are no longer just administering and operating the finance, they’re taking over the delivery of care, using regulatory levers. Where there used to be many organizations and individuals, each responsive to the needs of their local community, decision-making and governance is now highly centralized.

Our health care system: “Government owned and operated”

Despite the fact that Canada has a mixed model of public and private health funding and service delivery, the overall administration and delivery of health care has steadily become government-centered, reflecting a series of large-scale administrative and regulatory reforms.

Most planning is done by the policy and planning units in the provincial government, including:

major new capital investments (e.g. hospitals and the equipment within them)

local infrastructure planning (e.g. community-based health facilities, nursing homes, etc.)

health human resource planning and management (e.g. contracts for doctors, nurses, and other health workers; location and size of medical and nursing schools; licensing and credentialing requirements; etc.)

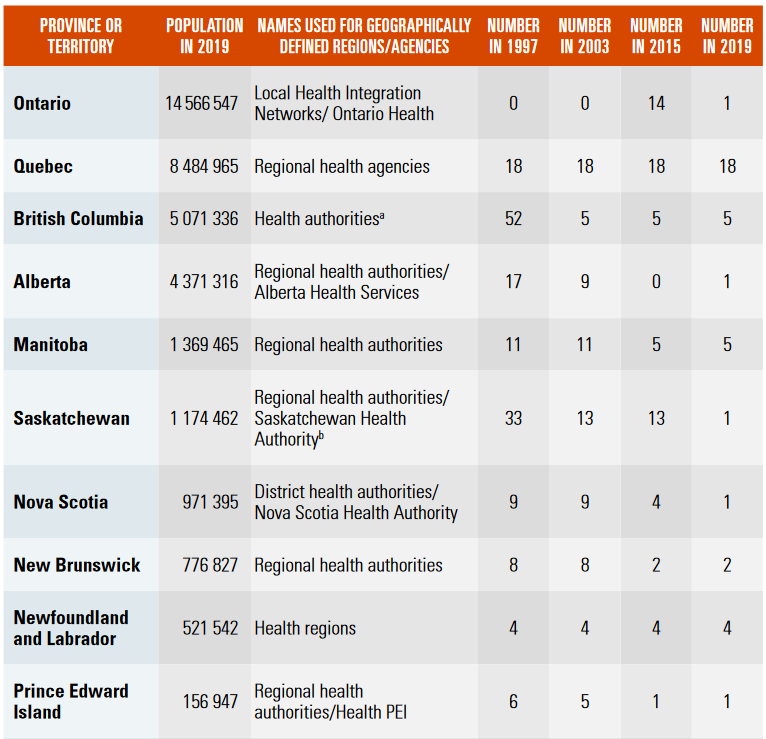

This high-level role of the ministries is complemented by more granular planning by the (supposedly) arm’s-length health authorities, which coordinate and administer the actual delivery of health services within a defined geographical area. However, as clearly shown above, those health authorities are decreasing in number, while becoming subsumed into the provincial departments of health.18

Sadly, there is little to no role for patients and the public in these planning processes, despite the fact that one of the stated objectives of regionalization was to increase public participation. The majority of decision-makers and administrators are appointed, without public consultation.

Furthermore, the same Department of Health that determines the budget for your local hospital also decides whether that facility should stay open and what services will be available, and then they decide whether or not those services are up to snuff. If that’s not a conflict of interest, I don’t know what is! And they do it without asking you!

To quote Laurel and Hardy: “This is a fine mess you've gotten us into!”

No wonder our system is a mess! It’s perfectly designed to get the results it gets.

Canada is heavily invested in the central design feature of “public administration”, pushing it well beyond the financing of Medicare as an insurance plan, as envisioned by the Canada Health Act.

The current working theory in government is that we require total state control of care delivery, administration, regulation and governance. Every time there’s a problem, the government “fixes” it by adding more rules and regulations, or by eliminating another layer of public accountability.

The more they micro-manage, the worse it gets.

We had a choice (and we still have a choice)

Other countries chose other roads, some less travelled, some more, and that has made all the difference.19

We should try something different.

More on that in the next post.

By Edward Demings, an American business theorist, composer, economist, industrial engineer, management consultant, statistician, and writer.

As a reminder, health care systems are classic examples of complex adaptive systems, which don’t respond to ever-increasing efforts to control everything. See previous posts.

“Hospital services”, for the purposes of the Act, includes inpatient care, outpatient diagnostic services (e.g. x-rays and lab tests) and outpatient treatments (e.g. hospital-based physiotherapy).

While it tempting to imagine that there was no public financing of health care prior to the inception of Medicare, in fact the provincial governments had a long history of providing subsidies to hospitals to admit and treat all patients irrespective of their ability to pay. The government of Ontario, for example, had the Charity Aid Act of 1874, worker’s compensation legislation in 1914, and then a medical service plan for social assistance recipients.

Examples in Canada include Accreditation Canada, through which hospitals evaluate each other, and various Medical Peer Review programs, in which doctors evaluate each other.

Canada has ten provinces and three territories. Being sparsely populated, the territories are heavily dependent on the federal government for their financing, so federal-territorial relations differ from federal-provincial relations. For simplicity, throughout the rest of this post I’ll simply refer to the provinces.

For the sake of brevity and readability, I’m going to lump dental surgeons in with physicians for the remainder of the post. The original insured dental surgeries were the ones done in hospitals, which is a small subset of the work done by dentists and dental surgeons.

As Medicare was debated, there was an alternative proposal (championed by Alberta, Manitoba and Ontario, as well as organized medicine) which would have involved targeted government subsidies for the purchase of private insurance.

Many were owned and operated by communities or non-profit organizations (i.e. religious groups).

The right to “self-regulate” is granted by government, which seems a bit unusual. It’s a social contract in which:

physicians commit to altruistic service, professional competence, morality and integrity, and to address issues of social concern, and

society grants to individual physicians and the profession considerable autonomy in practice, status in the community, financial rewards, and the privilege of self-regulation.

In other words, government agrees to a “hands off” approach, in exchange for the profession policing itself for the public good.

A significant number have incorporated as professional corporations, mainly to increase their after-tax income. This further complicates the question of whether their practices are “non-profit” entities.

Some provinces have prohibitions on practice outside the Medicare system. Most simply limit the ability to bill “above tariff”. In other words, a doctor is welcome to charge the patient directly for their services, with the patient then seeking reimbursement from Medicare, but the doctor cannot bill more than what the province would pay. When fees remain the same, doctors have no financial incentive to leave the public system.

Various services get “de-insured”, when funds are tight. Other services are paid for only when the procedure is done in a specific location. Our Nova Scotia government, for example, in seeking to block a private abortion clinic, created regulations listing a number of procedures that could only be done in hospitals, abortion being one of them.

The shortfall is MASSIVE, with no prospect of it improving anytime soon. According to Health Canada, we are short 25,000 family doctors, and we graduate 1362 per year. You do the math!

It’s worth noting that we also have fewer practicing nurses than other countries.

Looking at my personal experience, having turned 65 I’m eligible for our provincial seniors pharmacare program. There’s an income-based “premium” for this “public” program, which has limitations on its coverage. Because I’m now eligible for that program, even if I choose not to participate, I can no longer obtain drug coverage through my private health insurance. I suspect, over time, my private insurance will also stop paying for my dental care, because there’s a public program available.

Here in Nova Scotia, where our government was elected on a platform of “fixing health care”, their first act was to fire the CEO of the provincial health authority and replace the governing Board with a government-appointed “administrator”. Several years later, there’s no visible separation between the Department of Health and the “arm’s-length” Health Authority. Alberta has pulled the same trick, several times in succession!

With apologies to Robert Frost.