My last post concluded with the observation that our health care system is built around elaborate structures that focus solely on numbers and counting, without actually meeting the fundamental needs of the patients.

Don’t get me wrong, numbers ARE important.

However, we don’t measure the single OUTCOME that matters most to the patients: “HOW QUICKLY DO WE PROVIDE THE HELP THE PATIENTS NEEDED?”

The things we measure are proxies for what matters. As is always the case, when you choose what to measure and then set numerical targets, what gets measured becomes what’s “important”. There are lots of ways to make the numbers look good, even when things aren’t going according to whatever plan there is.1

These problems aren’t new. For example, in an episode of the satirical British TV series “Yes, Minister”, the Deputy Minister of Administrative Affairs, Sir Humphrey Appleby, explains to the Minister, Jim Hacker, why the brand new 1000-bed St. Edward’s Hospital has been operating for 8 months with 500 administrative and technical staff, but no clinical staff and, most importantly, no patients.

“…we don’t measure our success by results, but by activity. And the activity is considerable. And productive. These 500 people are seriously overworked - the full establishment should be 650. May I show you some of the paperwork emanating from St. Edward’s Hospital?”

While that 40-year-old example is fictional, it’s not far off the truth.2 You should see the paperwork! Just look at this glossy Nova Scotia Health Authority document about their “Quality, Safety and Performance Framework”. Take heart in the recent government announcement about a new “Health System Performance and Accountability Council”. Clearly, we take this seriously!

However, what you see on our provincial “Action for Health - Public Reporting” website is a large number of statistics about emergency department (ED) ACTIVITY, but nothing about RESULTS. Sir Humphrey would be proud!

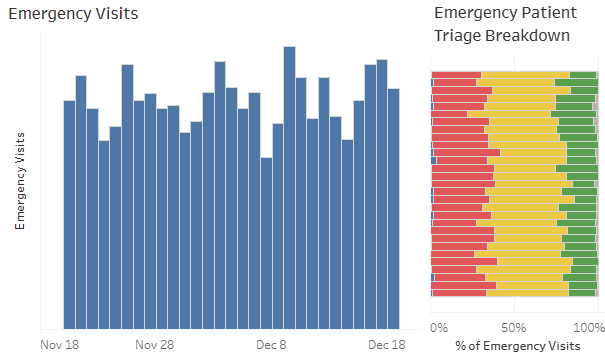

We are told the total number of visits to each ED, and the breakdown of those visits by the triage score.

Note the absence of a vertical scale on the left-hand graph; in the live version, you have to hover over each bar to see the corresponding number. The daily ED numbers for this hospital average about 135, with regular and significant dips every Saturday.3 The right-hand graph showing how sick the patients were is color-coded, with blue (barely visible on the left) being the highest acuity (CTAS 1) and gray (barely visible on the right) being the lowest acuity (CTAS 5). Even though the CTAS levels were specifically designed to guide the urgency of patient assessment and treatment, what we aren’t told is how quickly the patients were actually seen, or what actually happened to the patients in each grouping.

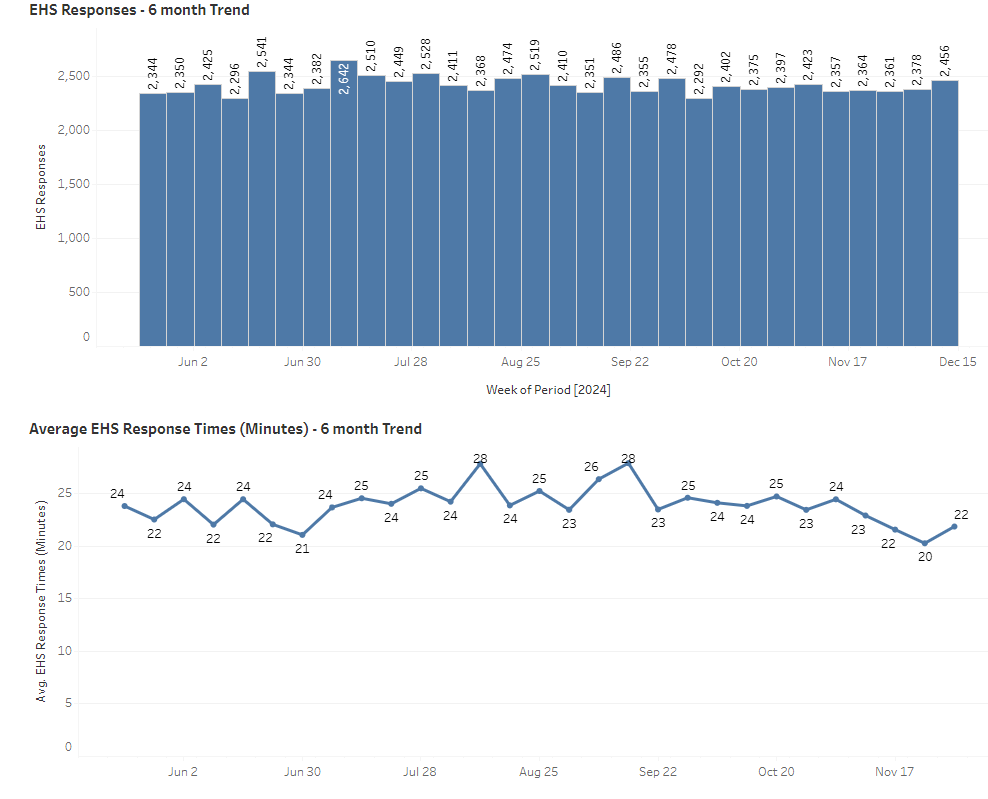

Similarly, we are told about the number of 911 calls for ambulance services and their average response times. Of note, the numbers don’t vary much from week to week.

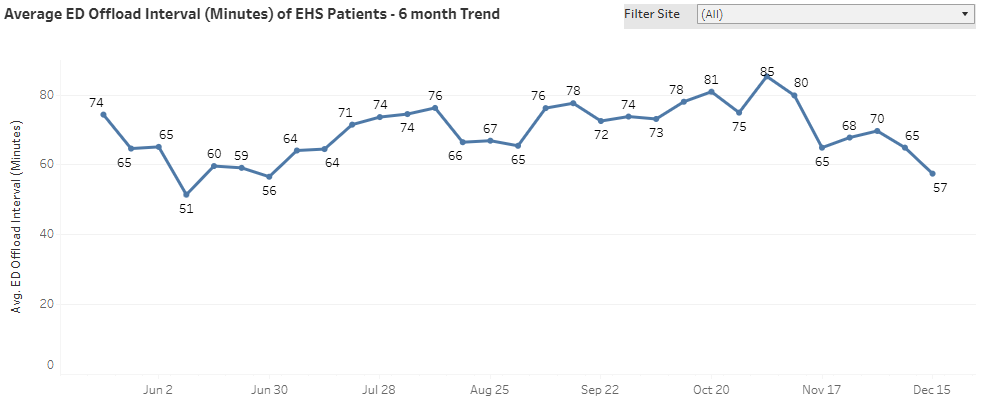

Finally, we can also see where the ambulances “offloaded” their patients (which makes them sound less like people and more like some sort of cargo) and how long, on average, it took to do so. While the graph below shows the province-wide average offload time to be about one hour, the numbers fluctuate randomly for each hospital, and they vary considerably from one hospital to the next.

Internally, and not for public consumption, the bureaucrats review reports about whether individual EDs are meeting their budget targets, the levels of staffing, the number of vacant positions, the amount of overtime claimed, the number of patients who left without being seen, how long it takes for patients to be seen by a doctor, how many patients are held in the ED pending the availability of an inpatient bed, how long those patients wait, how many patients died, etc. Sometimes they get fancy and look at “percentiles” rather than numbers or averages, as when they say that the 90th percentile for ambulance offload times was 158.5 minutes in 2024, as compared to 284.5 minutes in 2023.4

All that ACTIVITY is great, but people go to the ED ONLY because they are worried about their health, for some reason. The OUTCOME that matters to the users is how fast the system can get worried patients in and satisfied patients out the door, with their symptoms relieved, their questions answered, a diagnosis made, and treatment given.

However, nobody asks the patients leaving the ED whether they got the help they needed in a timeframe that seemed reasonable to them.

The near universal complaint, from anybody who has ever been to the ED, is how long they had to wait. Some people don’t complain, but that’s generally because their wait was “less than expected”, meaning that they “only” spent 6 hours in the ED and not 12 hours, as they had feared. Waiting for emergency care (and receiving slow care) is now the accepted norm, the justification being that EDs across the country consistently face “high patient volumes which exceed their capacity”, meaning that they operate at high utilization rates.5 If your bank had this problem (more customers than tellers), they would add tellers. In health care, rather than fixing the underlying problem by matching ED capacity to patient demand, the response has been to introduce a labor- and time-intensive triage system, the entire purpose of which is to decide how long the users can be made to wait!6 Unsurprisingly, because we can document that some people wait too long, there’s now a separate policy and process to ensure that those waiting are reassessed regularly, to be sure that they can safely wait longer. There’s paperwork to prove it!

Imagine what would happen if McDonald’s, a place you go to get “fast food”, put one of their burger-flippers at the door to quiz you for 15 minutes about how hungry you are, before putting you into one of five different lines with different anticipated wait times. Those prone to hypoglycemia jump to the front of the line. Those who ate within the past two hours can languish in the waiting room. Meanwhile, with one less person flipping burgers, the service gets even slower. Does this sound like a good plan? With fast food, you have the option to go elsewhere. In our health care system, you don’t. You just get to live (or die) with the system we have.

So, why don’t the ED’s have sufficient capacity that they can quickly assess and treat people as they arrive, seeing the sicker ones first but otherwise operating on a first-come, first-see basis? We don’t need to triage you to see how long you can wait, when the plan is NOT to have you do any waiting. Faced with two people who arrive at the same time, you don’t need a fifteen-minute assessment to decide that the sicker one should go first, because the less sick one will also be seen quickly. I know, it sounds magical, but it’s been done!7

As for capacity versus demand, bear in mind that each ED eventually manages to assess and treat the patients who show up there each day (minus the 15% who leave without being seen, which is another statistic NOT publicly reported). That implies that each ED already has the staffing, supplies, and funds to look after at least 85% of the daily arrivals. The bottleneck is either space (not enough bandwidth to handle peak volumes, like rush hour traffic) or scheduling (the staff and resources are scheduled in shifts that don’t match when the patients actually show up). Space could be freed up by moving patients along efficiently (no unnecessary waiting!) and getting admitted patients out of the ED quickly. Staff could be freed up by better scheduling and/or cutting back on wasteful processes, like triage and those waiting room reassessments, among other things.

However, all of that would mean changing the way things are done, and change doesn’t come easily in health care. After all, the triage system is “policy”. Waiting is the foundation of the system, because demand exceeds capacity. That’s our excuse, and we’re sticking to it! We need the data, and the forms have to be filled out. Never mind that paperwork is just an activity that consumes valuable resources. Activity is what we count. And God forbid that we run over budget without “justification”. However, being overwhelmed is considered to be a good excuse, and the paperwork can be overwhelming; run behind, and you’ll probably get extra staff!

In my time in administration, I did see the occasional “patient satisfaction survey”. There might have been one question about the timeliness of care buried in among a whole bunch of other questions. Unsurprisingly, the patient satisfaction was generally pretty low. Such surveys are rarely reported publicly.

Given that the medical consequences of delayed care include embarrassingly bad outcomes, including death, you’ll see even fewer public reports about the actual OUTCOMES of all that waiting for care. Some do, however, hit the press, as with this recent news report about a poor soul who died after he decided to leave the ED after waiting too long for a diagnostic test.

To be blunt, we waste a lot of time, effort and money counting the patients (even when the numbers don’t change much), documenting how poor their care is (in the name of “prioritizing” those who need it the most), and counting and conserving resources we know to be inadequate (in the name of balancing the budget), all the while wondering why the staff and patients are measurably unhappy.

We are so busy with the paperwork that we don’t have time to confront the actual causes of the problems. Demand exceeds capacity, but we don’t have the time or the money to reduce demand or increase capacity. Never mind that the system exists to serve patients and we are wasting vast amounts of resources on useless activities.

Having gathered all that data, there’s a general assumption that making all the numbers “better” will mean that the system of care is producing better results. There are any number of reasons why that’s not true.

For one thing, we tend to measure the things that lend themselves to measurement, even when the measurement is useless, unreliable, and/or out of our control. In the graphs above, for example, we count the number of patients seen, something largely beyond the control of the emergency department. There are a lot of emergency visits, but are they appropriate emergency visits? Does every one of those patients actually need to be seen in the emergency setting? What would happen if they had alternatives? The numbers have drifted slowly upwards over time, as you might expect in a province where the population is growing, but, beyond that, the numbers themselves aren’t particularly enlightening. Similarly, the triage scores, while considered to be “objective”, in fact vary considerably from person to person and site to site, with one systematic review suggesting that over 40% of patients were “mistriaged”.8 Furthermore, triage scores can creep upward over time, particularly when ED funding models are built on the number of patients seen and their CTAS scores. Seeing more patients means you get more money. Seeing sicker patients (as judged by the CTAS scores) also means more money. Saving more lives won’t get you more money.

Furthermore, as a complex adaptive system, the health care system can either “buffer” or “exaggerate” the effect of any single change targeted at any specific number. When their response times are excessive, the Department of Health financially penalizes the arms-length company that manages the ambulance service, but clearly the response times for new calls are affected by the time it takes to offload patients at the hospital. They get additional funding to add vehicles and staff, causing the staff in emergency to become even slower at offloading patients, in part because they feel underfunded and understaffed. You add staffing to the ED to look after the admitted patients who aren’t leaving the ED quickly, but then the inpatient units get even slower at accepting new patients.

Beyond that “organic” behaviour of the complex adaptive system, there’s also room for “gaming”. Hospitals in the UK, for example, when faced with a mandate to move admitted patients to an inpatient bed within 12 hours of arrival in the ED, responded by reclassifying ED stretchers in the hallway as “inpatient beds”. Similarly, when faced with a mandate to have ED physicians see their patients within 4 hours of arrival, some UK hospitals responded by not registering patients arriving by ambulance until they were confident they could be seen within 4 hours. I’ve heard about similar behaviours here in Canada.

Lest anybody accuse me of unfairly picking on the emergency department, these problems with waiting and with measuring the wrong things are absolutely NOT unique to emergency care. They permeate the entire healthcare system. Each silo, emergency being but one among many, focuses on its own batch of process (or activity) measures while managing to ignore the fact that the entire system exists to serve the needs of the patients, who, by and large, wait far too long and aren’t happy about it.

In Canada in 2024, as in “Yes, Minister” in the 1980’s, we still don’t measure our success by results. We measure activity, and there’s lots of it!

More fundamentally, we pay for activity, not for results.

You get what you pay for.

The solutions are obvious, but we won’t see any change as long as the system revolves around money rather than patients.

The communists were masters at this, with their five-year plans, etc., but the skillset lives on, even in democracies. For a detailed discussion of the problem, see “WHAT’S MEASURED IS WHAT MATTERS: TARGETS AND GAMING IN THE ENGLISH PUBLIC HEALTH CARE SYSTEM”

I could tell you about a few hospital expansions in Nova Scotia that were completed long before any patients were actually admitted. Our government doesn’t always allocate the necessary operating funds, even when they know, years in advance, that a bigger hospital will require additional staff, supplies, etc.

However, I wouldn’t be surprised to learn that the staffing is the same on Saturday as for every other day.

In this case, note the pseudo-precise numbers, which imply that we can measure ambulance offload times accurate to 1/10 of a minute, which is 6 seconds!

As one article put it, “Emergency department (ED) overcrowding has been a prevalent issue for several decades in hospitals around the world. The alarmingly overcrowded status in the United States health care system has been well documented. Canada, which operates a universal publicly funded health care system, is no exception. Overcrowding occurs when demand exceeds available capacity. Given the limited capacity of many EDs, some patients may experience excessive wait times which can be critical, even life threatening.” You might reasonably ask why the problem has been allowed to fester for decades. The workers within the system and the patients who use the system have all come to accept that there’s no other possible way for the system to work. It’s “learned helplessness”.

The original purpose of triage was to QUICKLY sort out injured soldiers, recognizing that, during a battle, the number of casualties would TEMPORARILY exceed the available medical care. Care was to be directed to those who would benefit the most, with the fatally injured left to die and those with non-life-threatening injuries left untreated.

In health care, it’s called “See and Treat”. Google it. It’s been tested and proven in multiple places. In manufacturing, Toyota calls it “Just in Time” production, wherein “waiting” at any stage of any process is considered to be a form of waste, to be eliminated.

Two-thirds were “over triaged”, which could be interpreted as “erring on the side of caution”, while one-third were “under triaged”, which places seriously ill patients at risk for delayed treatment and/or undertreatment.

'Yes Minister' remains a work of genius ......glad to see it made it across the pond! A contemporary version would have to add the much diminished ability of the idiocracy, the malign politicization of the civil 'servants', DEI and woke....it would take more genius to make that funny, eh?

Another great read thanks Rick!!