I read the news today, oh boy!

(For the edification of younger readers, “I read the news today, oh boy!” is a line from “A Day in the Life”, a whimsical but somewhat downbeat song about listening to the news, released by The Beatles back in 1967 or thereabouts).

Our news is depressing! Consider:

A news item out of Quebec, where 2.1 million people do not have a family doctor. Because 500,000 of them have “major or moderate health problems”, the provincial government is considering changing how family doctors are assigned to patients. ONLY those with complex or chronic conditions (such as cancer, mental health issues, cardiovascular disease or diabetes) would be assigned a family doctor. ALL others (including those who currently have a family doctor) would have to call a Primary Care Access Point, which would direct them to the “most appropriate resource”. This change would “transfer” up to 1.5 million annual appointments from patients who have a doctor to those without.

An announcement in Nova Scotia, where the Premier says a “first of its kind in North America” clinic-based program will assess the skills of international medical graduates, reducing the assessment time for prospective candidates to about 12 weeks from the current 18 months. Dr. Gus Grant, of the College of Physicians and Surgeons, assures us that "This clinic will open the door wider for physicians to be assessed for licensure, but it will not lower the bar of competence or quality that we require of our physicians."

An announcement that the new medical school at Toronto Metropolitan University will use a “multifaceted, holistic approach to identify students who possess the necessary academic capabilities, interpersonal skills and personal attributes required to excel in the medical profession”. The majority of admissions will come through three admissions pathways (Indigenous 25%, Black 25%, and Equity-Deserving 25%), which have been created to account for systemic bias and eliminate barriers to success. A minimum Grade Point Average of 3.3 in any undergraduate degree is required1 (again, to minimize barriers and create an inclusive and diverse learning environment). There will be no requirement for the Medical College Admission Test, the standardized, multiple-choice test that has been a part of most medical school admissions processes for decades.

Professional Standards Regarding Conscientious Objection, published by The College of Physicians and Surgeons of Nova Scotia, in May 2024. These require physicians to make “effective referrals” to someone else when they are personally unable or unwilling to provide legally available treatments that conflict with their personal, ethical and or religious beliefs (as for example, when the patient is seeking an abortion, medical assistance in dying, etc.)2. In effect, if your patient wants euthanasia and it’s against your personal, ethical and or religious beliefs, you’re still required to make the necessary arrangements.

Another announcement in Nova Scotia, where more pharmacies will provide care for minor ailments and illnesses as part of a provincewide pilot program. Services offered include assessment and prescribing for minor illnesses (like Strep Throat, Pink Eye, Urinary Tract Infections)3, Chronic Disease Management (including Diabetes, Asthma, COPD), prescription renewals for all medications, and publicly funded vaccines for adults and children and medical injections. Other similar local initiatives involve midwives, nurse practitioners, nurse prescribers, and various forms of “virtual care”.

There’s a common thread in these items. I’ll explain later.

Meanwhile…

As these events were unfolding, I was chatting online with a group of colleagues.

One of the younger ones observed that, for those of us in the “older” generation4,

“Medicine was even more than a profession; it was a calling. It was seen as an honor to part of this sort of sacred guild that society put so much trust in.”

He went on to say

“Since then, it is increasingly seen as just another job, including by most of the doctors graduating. Today’s young family doctors (and specialists increasingly) don’t see themselves as free thinking physicians out on their own, entrusted with their patient’s health and advocating for them, working long and hard hours and making personal sacrifices because they were called to be part of this special and time-honored guild. They’re happy to just slide into another governmental bureaucratic hierarchy, do what they’re told, collect a cheque and take their negotiated holidays. Now it’s just a job to them, and to government.”

Finally, referring to some of the changes afoot, he observed

“The other scary component is the willingness of doctors, especially and increasingly the newer generations, to play along.”

There followed some discussion about whether this was a generational phenomenon. One of the (self-described) middle-aged doctors said

“…in my opinion, the younger generation of docs are much more of the "it's all about me" philosophy. Not blaming them, because we've raised them to be that way. We get them to focus on their feelings, pursue their "best life", go on and on about "physician wellness" and "work-life balance". Not shitting on any of those things 100%, as they are all important and valuable in some way. But life is also about service and giving back to your community, your patients, your society. Nobody demanded that you be a doctor, so one should have a sense of service, not entitlement. I constantly see young docs talking about how we are underpaid and underappreciated. I think about my family doc growing up (his kids were my friends) who delivered babies at 3AM, got called to ER to see his patients at all hours, did inpatient rounds every morning, was in clinic every day, and hardly ever took vacation. Yes, he was well paid, but my god he deserved it! Now I see a generation of new grads in Family Med doing hospitalist work every 2nd week, making 330K per year. Or palliative care pulling down 1600 bucks per day to see a handful of patients with zero time pressure. And then complaining about how hard done by they are. We have become a bunch of entitled prima donnas.”

So, has medicine become “just a job”? If so, then what matters is working conditions, remuneration, and benefits (and not being underpaid)!

Or is medicine still “a calling”? That would mean that what matters is belonging, autonomy, service, and sacrifice (and not being underappreciated)!

What does it mean to practice medicine?

The answer, in part, is that medicine is a “self-regulated profession”.

I venture to say that most people don’t know what that means, including the younger doctors!

Let’s go through it, step by step.

Looking at a Nova Scotia government guide (with emphasis added):

“Self-regulation is a privilege granted to professions in the public interest. Professions do not have a “right” to regulate themselves. Rather, self-regulation is one of many instruments government may choose in an effort to protect the public and reduce risks associated with incompetent and unethical practice.”

and:

“Self-regulation comprises two key elements: the authority to register and license members; and the authority to investigate and discipline them….

The powers and duties conferred on professions vary considerably, but usually include at least the power and duty to:

Govern and manage the body charged with overseeing the profession;

Set standards and requirements to be met by those wishing to enter the profession;

Set standards of practice for members of the profession;

Make and enforce rules with respect to complaints investigation and discipline; and

Prosecute offences under its legislation.”

and, finally:

“Members of a self-regulated profession (sometimes referred to as “registrants”) have, in all circumstances, an ethical and legal duty to put the interests of clients/patients and the general public ahead of their own interests.”

For any profession, self-regulation limits competition and increases the costs of services. It grants a professional group a monopoly of sorts. That being the case, the privilege to self-regulate is generally only granted when:

the profession can demonstrate that it exercises a defined body of knowledge and skills,

generally acquired through specific education and experience,

which does not overlap significantly with that of any other profession, and

there are real and substantial risks of harm to individual consumers or clients when practitioners lack the appropriate knowledge and skills.

Or, as somebody else suggested:

“There has been a surprising degree of agreement on the fundamental nature of the relationship between medicine and society. Virtually all who have described it state that society has granted medicine autonomy in practice, a monopoly over the use of its knowledge base, the privilege of self-regulation, and both financial and nonfinancial rewards.

In return, physicians are expected to put the patient’s interest above their own, assure competence through self-regulation, demonstrate morality and integrity, address issues of societal concern, and be devoted to the public good” (Cruess and Cruess, 2008)

To protect the public from people who profess to be doctors but don’t actually know what they are doing, a significant chunk of self-regulation involves setting and upholding standards:

for people entering the profession (through registration and licensing, which generally require proof of specific training and competence), and

for those practicing the profession (through standards of practice and discipline).

In Nova Scotia, as in most provinces, that self-regulatory role is served by the College of Physicians and Surgeons of Nova Scotia.5

Self-regulation is one part of a social contract

Some describe the relationship between the medical profession and the public as a “social contract”, involving expectations and obligations on both sides, some implicit and some explicit, some written and others unwritten.

In all countries, the explicit parts of the contract include:

codes of ethics,

legislation outlining the structure of the health-care system,

the laws establishing the self-regulatory framework for licensing, certification, and discipline, and

legal decisions relating to medical care.

The implicit elements of the contract, including altruism, commitment, and independent professional judgment, come from within and cannot be legislated.

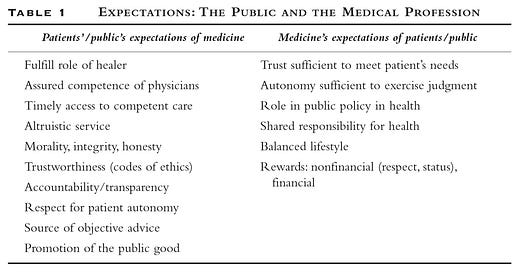

The social contract has evolved slowly over time. In the fullest sense, the current expectations and obligations of the profession and the public are approximately as listed in the following table:

Individual physicians become parties to the social contract because they belong to a “community of practice”, something they voluntarily join while pursuing their education and training. As they do so, they come to accept the norms and values of the profession, earning the right to call themselves “doctors”. Their leaders “negotiate” the social contract on their behalf, ensuring that they respect the importance of the public good while maintaining medicine’s professional status.

So, looking at it that way, both of my colleagues were correct. Medicine is both a job and a calling, and the situation is evolving.

The social contract is changing, perhaps not for the better

In reality, there’s no longer a simple relationship between the patient and their doctor, or between the public and the medical profession.

“Major changes have occurred in physician autonomy and accountability. In earlier times physicians were accountable primarily to their patients and their colleagues. They are now accountable to governments and commercial organizations for their competence, performance, productivity, and the cost-effectiveness of their activities” (Cruess and Cruess, 2008)

In Canada, the government now serves as the principal payor of physicians and the operator of a significant chunk of the health care system, on behalf of the public. As one example, you might be fully trained and eligible for a license to practice in Nova Scotia, but you won’t be able to work unless the government, through its various agencies, grants you privileges and a billing number.

Various patient advocacy groups create additional expectations, often telling patients what care or services to request.

On the physician side

“…the medical profession consists of individual physicians and the many institutions that represent them, including national and specialty associations and regulatory bodies. Within the circle chosen to represent the medical profession is found a myriad of firmly held opinions, vested interests and political orientations. Individual physicians often disagree with the associations that represent them; generalists and specialists may have different desires, and there are often regional differences of opinion.” (Cruess and Cruess, 2014)

So, it now looks a bit like this:

So where does that leave us?

Going back to the events that I described at the start of this post, you can see where government and societal pressures are changing the social contract:

In Quebec, the proposed change in how family doctors are linked to patients would dramatically alter the relationship between individual patients and their chosen provider, severely limiting the autonomy of both physicians and patients, all in an effort to improve timely access.

In Nova Scotia, the Premier’s announcement of a new program to assess the skills of international medical graduates raises questions about the ability of the supposedly self-regulating medical profession to set its own standards for people entering the profession, even though Dr. Grant assures us that this will not lower the bar of competence or quality.

Similarly, Toronto Metropolitan University’s experiment with “equitable” admissions, including lower academic standards for admission and eliminating the requirement for the Medical College Admission Test, raises further questions about the profession’s ability to define its own standards. What happens if their graduates turn out to be less competent?

In the case of Conscientious Objection, the self-regulating College of Physicians and Surgeons has determined that certain services (such as euthanasia and abortions) promote the public good, justifying a severe limitation of the individual physician’s ability to exercise their personal judgment. Were physicians consulted about this, or was it a response to public pressure? Medical Assistance in Dying is fairly new in Canada, the landscape is evolving, and what was deemed unethical or illegal a few years ago is now deemed ethical and legal. Is there really no room for debate or conscientious objection?

As for pharmacists providing medical care for minor ailments and chronic illnesses, it seems clear that some no longer believe that doctors have a clearly defined body of knowledge and skills, acquired through specific education and experience, which does not overlap significantly with that of any other profession. Whatever it is that doctors do, others are willing to do it for less6, and the government is happy to pay them! Do pharmacists have the training to examine and treat patients? Have they got the necessary facilities? Given that pharmacists will end up prescribing the medications that they will then dispense, will they be objective in their treatment advice?

In conclusion…

The longstanding relationship between physicians and society is rapidly evolving.

“Many of the expectations of the… parties have been present since the modern professions were established by licensing laws in the mid-19th century, but there have been dramatic increases in the nature and magnitude of the expectations and changes in how they are expressed.

Societal expectations have increased because modern science has given the healer greater capacity to cure, increasing medicine’s importance to the average citizen.

Physicians have also altered their expectations from the 19th and early 20th century when physician incomes and status were relatively low. New expectations have been the added to the contract, such as the desire of individual physicians for a balanced lifestyle and the expectation that physicians will participate in team medicine.

In addition to the changing expectations of the various parties, the expectations of one party may conflict with those of another. An example is the realization that younger physicians of both sexes wish time for family and outside interests. This may conflict with the altruism fundamental to the practice of medicine”

My personal theory is that this massive upheaval accounts for much of the dissatisfaction (or “burnout”) that we see in doctors today. They’ve lost their autonomy, the respect of the public, and the benefits of being self-employed.

Doctors aren’t asked by government what should be done. They are increasingly being told where to work, who to work with, what to do and how to do it, often in the face of severely constrained resources.

While the medical societies, like DoctorsNS, see this as a matter to be resolved through contract negotiations, it’s a much, much bigger problem. More on this in future posts.

In “exceptional circumstances”, applicants in the Indigenous, Black, and Equity-Deserving admissions pathways with a GPA below the minimum requirement of 3.3 may still have their application considered.

Going further, the physician must continue to provide care to the patient until care is no longer required or wanted, or until another suitable physician has assumed responsibility for the patient, or until after the patient has been given reasonable notice that you intend to terminate the relationship. Because their Professional Standard and Guidelines for Ending the Physician-Patient Relationship limits the circumstances in which a doctor can actually end the doctor-patient relationship and includes the requirement that the doctor continue to provide some forms of care until care is transferred to another doctor, it’s nearly impossible to end the relationship!

Of note, some of the eligible conditions don’t necessarily require prescriptions, but you might ask whether pharmacists are really going to tell patients NOT to take drugs.

The older generation that remembers The Beatles.

Other physician organizations advocate for their members. In Nova Scotia, for example, Doctors Nova Scotia:

Negotiates physician remuneration with the provincial government,

Acts as the medical profession’s united voice on health-care issues that affect physicians and their patients to the public, health-care stakeholders and the government,

Influences and supports the development of health-care policies,

Offers programs and services to support physicians throughout their career, and

Offers a comprehensive package of member benefits and services.

In some cases, it’s debatable whether the non-physician providers are, in fact, any cheaper. That’s a subject for another post!

Having read this and the Pairodocs latest I conclude that we have in fact reached the point where medicine is no longer a profession. It retains some of the trappings, as does democracy in nations increasingly controlled by global elites, managerialists and lawyers, but it is now regulated and controlled, not self regulated, with no tolerance for dissent. Major changes such as MAiD are imposed with no proper consideration, debate or discussion within the profession. Calls for caution are regarded as obstruction of progress. Even if physicians wanted to stop this, and I fear most do not, it is too late

How soon will we have "bare-foot" doctors servicing the rural areas? A couple of years of at community college should be able to pump them out by the tens of thousands.